I didn't just visit Jaffna in Sri Lanka. I returned to it, like a forgotten verse in a prayer whispered by generations.

The palmyra trees still stood like old soldiers, their fronds rattling like memory in the wind. And the sun? It wasn’t just hot. It was righteous.

There is a wild charm to this place. Jaffna doesn’t seduce you gently; it grabs you by the collar with one hand, a toddy bottle in the other, and says, “Come see what the war couldn’t kill.”

We began in the heart of town, where my base was split between two wildly different but equally enchanting retreats. Jetwing Jaffna, that sleek tower of glass and hospitality, felt like a lighthouse in a land still finding its bearings.

Mahesa Bhawan meanwhile is not just a villa, but a house with memory baked into its walls. Built in 1935 by R.C.S. Cooke for his beloved Maheswari, it is now a shrine to time and taste.

From the rooftop at Jetwing, I watched the city’s pulse beat below. Men zipped past on mopeds with sarongs billowing like capes. Fruit vendors barked. Bells rang from kovils (temples). The scent of incense mixed with diesel.

And everywhere, the stoic grace of the people of Jaffna – resilient, sharp-eyed, quietly proud.

No journey here is complete without walking the sacred grounds of the Nallur Kandaswamy Temple. The gopuram, towering like a saffron flame, is a riot of stonework and devotion. Sanathi, the inner sanctum, thrums with an energy that can’t be explained, only felt.

I watched a young boy light camphor, his hands shaking slightly, his eyes unblinking. He wasn’t just praying. He was bargaining with the universe.

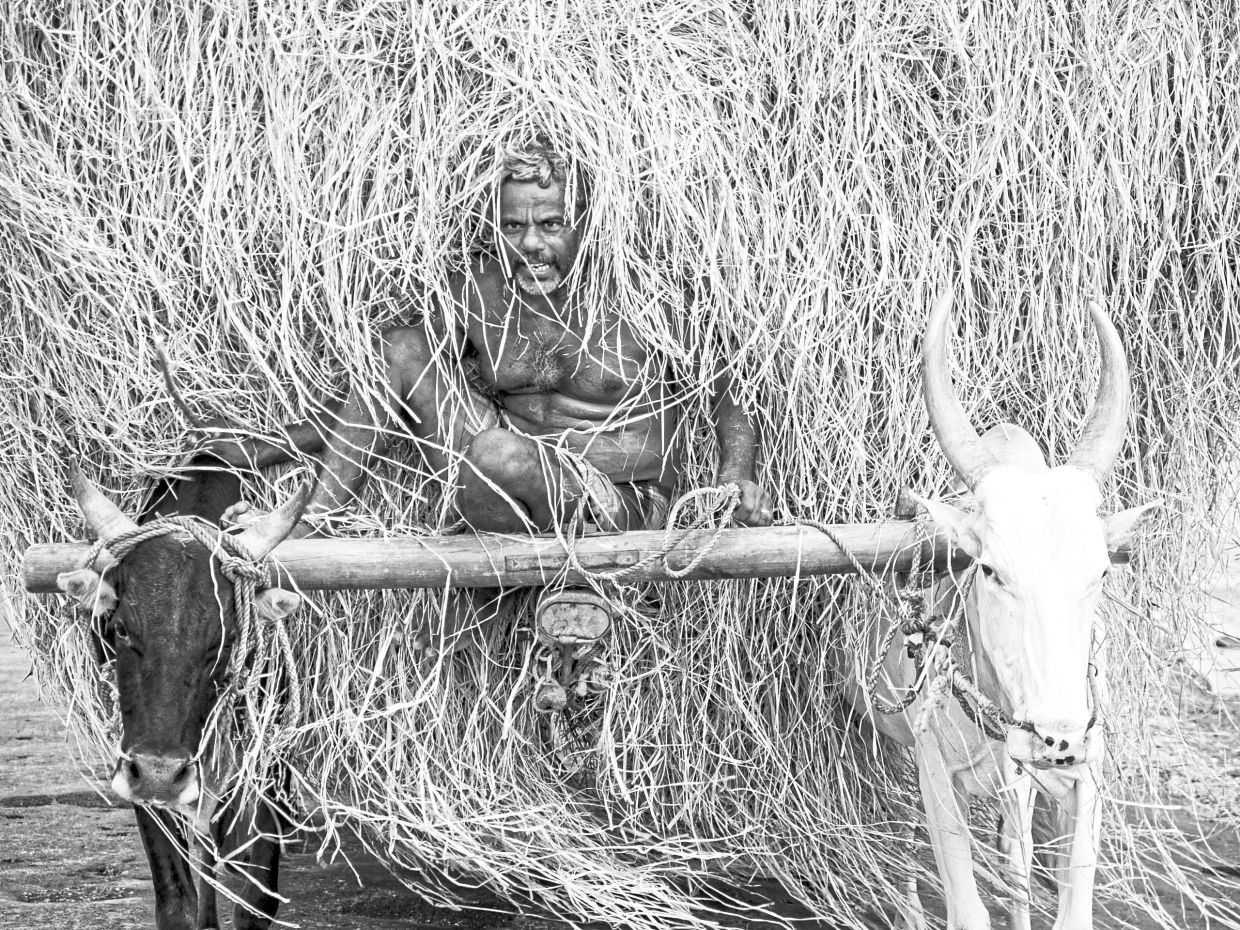

A few kilometers out, the landscape changes. Roads narrow, the trees thicken. Palmyra groves line the paths, their jagged leaves whispering stories of tappers who climb at dawn with no harness, just a rope around their waist and faith in their feet. They bring down the nectar which becomes toddy after a night of fermenting in clay pots.

The first sip is always a surprise. Earthy. Sharp. Honest.

I had mine under a tree in Karainagar, with a fisherman named Suthan who spoke of tides the way poets speak of heartbreak. He pointed out to Casuarina Beach, where the water is so still it feels staged.

Further up north, you reach Keerimalai Springs – natural freshwater pools nestled beside the sea. Legends say the waters are healing. I saw a man in his 70s lower himself into the pool, eyes closed, as if in conversation with the gods. And maybe he was.

Back in town, the culinary rhythm of Jaffna asserts itself unapologetically. No seeni sambol (a type of onion sambal) here. This is the land of kool, a seafood broth thickened with palmyra root flour, spiced with tamarind and turmeric, and best eaten with your hands.

The crab claws fight back. The prawn shells whisper secrets. There’s also mutton poriyal, rich and dry; kathirikkai (brinjal) with burnt garlic; and the peerless vellai paniyaram, a rice flour fritter that defies all logic by being both crunchy and cloud-like.

Jetwing Jaffna, to their immense credit, gets this. Their chefs have leaned into the local larder with no apologies. Breakfast includes idiyappam with crab curry, and lunch might bring poondu kulambu (a type of curry) so fiery it’ll make your ancestors sweat.

And then there’s Mahesa Bhawan, where dinner feels like a private concert. You don’t order off a menu, you surrender. They bring you what the land and sea gave them that day.

One night it was fresh white snapper grilled in banana leaf with a coconut sambol so vivid it could sing.

Jaffna isn’t easy, it never has been. The war took so much – the tsunami added insult. But still, the temples shine. The bicycles glide past old colonial bungalows. The markets hawk mangoes and dried fish. The cemetery walls speak of lives cut short and others defiantly long-lived.

The Jaffna Fort still looms, weather-beaten and stubborn. Built by the Portuguese, expanded by the Dutch, it has seen more conflict than most generals. Today, its ramparts make a fine spot for a sunset, even if the surrounding grounds are littered with debris and broken promises.

There are other pilgrimages too: The Jaffna Library, for example. Once one of the most complete and precious repositories of Tamil literature in South Asia, it was burnt to the ground in 1981 in an act of calculated cultural erasure.

It has been defiantly rebuilt and today, it stands not just as a library, but as a monument to resilience, proof that ideas cannot be razed and that words, like people, return stronger when they are buried with intent.

There’s also the Sivapoomi Museum, where Tamil history is preserved in silence; the alleys near the Dutch-era churches; and the daily ferry to Delft Island, a surreal outpost where wild horses roam and coral walls mark property lines.

At some point, someone will ask, “Why go all the way to Jaffna?” And the only answer worth giving is this: Because it’s still there. Not just existing, but insisting. In the food, the faces, the faded colonial relics, and the songs sung at kovil festivals.

But if you think that’s all Jaffna has to offer, you haven’t lingered long enough.

Spend a morning at Thirunel-veli Market. This is no quaint marketplace, it’s a living, heaving organism. You move with the crowd or get elbowed out of the way.

Carts teeter with jackfruit, coconuts, and mounds of red onions. Dried fish hangs like laundry, papaya juice spills on concrete and someone is always shouting.

Take the road toward Kantha-rodai, a field of silent stupas nestled in a quiet grove, eerie and moving. There’s no fence, no fee, just a field of domes watching the sky. Their presence says something about the many lives Jaffna has lived, and how faith here isn’t a tourist show. It’s sediment.

Drive west to Kankesanthurai Harbour, where rusting boats lie forgotten and the sea looks like it’s nursing an old wound. But there’s beauty in the stillness. Kids still dive off rock jetties.

If you find yourself in Point Pedro, the northernmost tip of the island, lean into the salt wind. The streets are lined with faded colonial facades and toddy shops that open before noon.

Back in the city, order a kothu roti served on yesterday’s newspaper. Let the rhythm of cleavers chopping on iron griddles become your soundtrack. Wash it down with sweet lime soda. Not everything has to be dramatic. Some things just need to be real.

And then there’s the statue – the one many drive past without a second glance, standing tall at a dusty junction where four roads wrestle for dominance. This is no ordinary roundabout. This is Sangiliyan Thoppu, and the man cast in bronze atop that pedestal is Cankili II – the last Tamil king of the Jaffna Kingdom.

His face is carved in stoic defiance. His hand grips a sword not just of steel, but of legacy. Once the sovereign of an independent Tamil kingdom, Sangiliyan fought tooth and nail, literally to the death, against the encroaching Portuguese in the early 1600s. When his back was against the wall, he didn’t flee.

He rallied and rebelled. He dared to dream that Jaffna could remain free.

They hung him in Goa in 1623. But they could never hang his memory.

Today, that junction, the meeting of Point Pedro Road-Muthirai junction, is a pulsing artery of the city where buses honk and young lovers meet. A coconut vendor does brisk business under the king’s watchful gaze. And yet, for those who know, it is hallowed ground.

Every time the wind tousles Sangiliyan’s bronze hair, every time the sun hits his sword it reminds us: Jaffna had kings once. And their stories were not written in Portuguese or Dutch or English. They were carved into the very soul of this land.

The views expressed here are entirely the writer’s own.

Abbi Kanthasamy blends his expertise as an entrepreneur with his passion for photography and travel. For more of his work, visit www.abbiphotography.com.