ABDUL Aziz Adamou carried his son Mohammadou urgently through the crowded hospital, the three-year-old limp in his arms.

The boy barely reacted when a nurse pricked his finger for a malaria test.

His mother, Nafisa, watched anxiously.

The day before, Mohammadou had been vomiting, soaked with fever and convulsing.

At first light, his parents climbed on their motorcycle and rode 30km to a hospital in Maroua, the largest town in northern Cameroon.

The malaria test came back positive.

Minutes later, a health aide administered an injection of artesunate, the World Health Organization’s recommended first-line treatment for severe malaria.

Over the next 24 hours, Mohammadou received two more injections and became alert enough to protest loudly.

Abdul Aziz grinned as he held his son still. After three days, the boy was strong enough to go home.

The drug that saved Mohammadou’s life was provided by the United States through a programme that dramatically reduced malaria deaths across Africa.

Last February, that programme was largely halted when the Trump administration shut down major components of US foreign aid, arguing much of it was wasted.

Supplies of artesunate quickly dwindled.

By the time Mohammadou received his dose, the drug had become nearly as precious as gold in northern Cameroon.

The far north has one of the world’s highest malaria death rates. Yet, years of sustained work, backed by American funding, reduced deaths in the region by nearly 60% between 2017 and 2024.

In 2025, political decisions made thousands of kilometres away in Washington threw that effort into turmoil, leaving more children sick, parents fearful and health workers scrambling to hold the system together.

That Mohammadou survived is testament to the commitment of local health staff – some of whom worked unpaid for months – emergency funding from new donors and luck.

Attacking malaria from all sides

The President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) arrived in Cameroon in 2017 as part of a US effort launched under President George W. Bush in 2005.

The aim was to end malaria deaths by deploying every available tool to the poorest communities, including the Sahelian village where Mohammadou lives.

Malaria has killed more people than any disease in history. Despite two decades of progress, it still claimed about 610,000 lives globally in 2024, almost all of them African children.

Washington invested heavily in PMI because of malaria’s immense human toll – and because reducing it helped stabilise fragile regions and project US influence.

PMI tackled malaria on multiple fronts – from testing mosquitoes for insecticide resistance to protecting pregnant women, supplying prevention medication for about two million Cameroonian children and training community health workers to diagnose and treat cases. A supply chain was built to reach even remote villages.

By the early 2020s, community workers were treating a quarter of all malaria cases. Early diagnosis meant fewer children developed deadly complications.

The scramble after the freeze

When news of the US aid cuts reached Maroua – the centre of the malaria fight – panic set in.

“Everything was lost,” said Dr Jean Pierre Kidwang, the regional coordinator of the National Malaria Control Programme.

Jean Marc Dahadai, a nursing assistant at the hospital where Mohammadou was treated, has worked there for 18 years.

“Ten years ago, in the rainy season, the whole compound would be full of malaria patients,” he said. “People on the ground, people in the yard.”

In recent years, he treated only one or two children a week as severely ill as Mohammadou.

“When I heard the US support was ending,” he said, “I thought we were going back to the way it was.”

Stocks of injectable artesunate began to run dangerously low just as the rainy sea

son – and the annual malaria surge – approached.

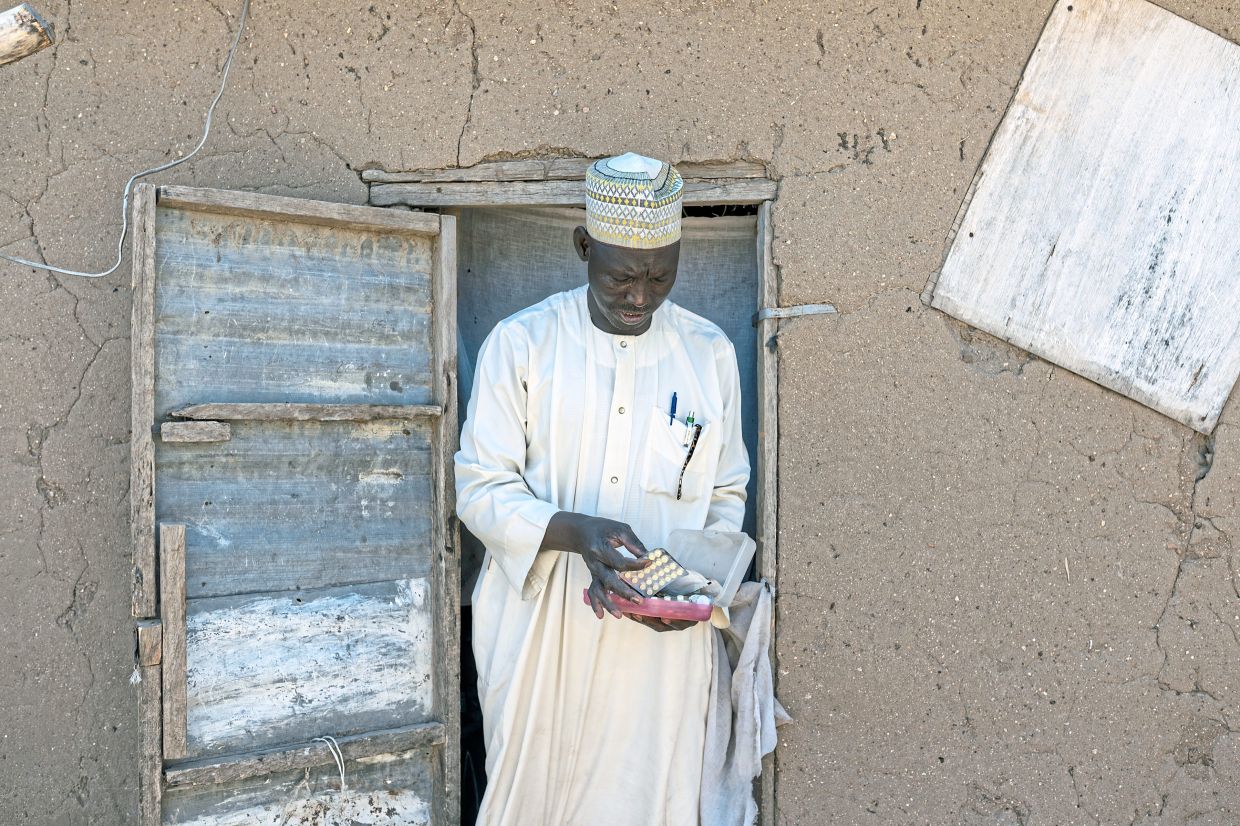

Parents called Kidwang asking when their children would receive the familiar blister packs of prevention medicine.

He had no answer.

PMI had already ordered Cameroon’s 2025 supplies before the freeze. The drugs were sitting in government warehouses – but there was no money or logistics to distribute them.

That was when, Kidwang said, the American non-profit GiveWell stepped in “like an angel from heaven”, funding emergency deliveries ahead of the rains.

Kidwang raced across the region, urging unpaid health workers to deliver the medication by bicycle, even in areas threatened by attacks from militant group Boko Haram.

Regular shipments of artesunate, however, did not resume.

Olivia Ngou, executive director of Impact Sante Afrique, said community networks reported deteriorating care and rising cases. Even chemoprevention, she said, arrived only sporadically.

Kidwang expected deaths to spike.

“They didn’t,” he said. “It shows a strong system was put in place.”

Fragile hope

In early December, Kidwang sat in his Maroua office reviewing reports of each child death that season: an infant whose family waited five days to seek care; a toddler treated with traditional remedies instead of artesunate.

In the corridor stood 19 boxes of leftover chemoprevention drugs. Each contained enough medication for 50 children and was stamped with an American flag and the words Gift of the American people.

Kidwang was saving them, unsure what would arrive next.

The Trump administration has said recipient countries must contribute more to health spending.

During the PMI years, Cameroon spent about US$2.1mil annually on malaria, compared with roughly US$22mil from the United States.

Cameroon, ruled by President Paul Biya since 1982, directs large portions of its budget to the military and servicing foreign debt.

In December, Kidwang heard cautiously hopeful news: the US State Department signed a health compact pledging up to US$399mil over five years, conditional on Cameroon boosting its own health spending by US$450mil.

The pledge is smaller than past US assistance – which totalled about US$250mil a year – but could help stabilise malaria programmes.

Funds would be channelled directly to the Cameroonian government, raising concerns among critics about oversight in a country consistently ranked high for corruption.

For now, malaria control is revving up again. Chemoprevention and artesunate have been ordered for the next rainy season and some health worker stipends have resumed.

Kidwang hopes it will be enough. He only has to look at the Adamou family to see the cost of failure.

Their district, Gazawa, had no PMI-supported community health worker. Mohammadou did not receive chemoprevention in 2025.Their mosquito net is torn. No one locally could test him when he fell ill. The local clinic did not have artesunate.

It was a chain of breakdowns, halted only when they reached a hospital still benefiting from the final threads of PMI support.

Mohammadou’s recovery shows what is possible when the system works.

“We saw the impact of what we can do,” Dahadai said. “We can’t just give up.”

— ©2026 The New York Times Company

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.