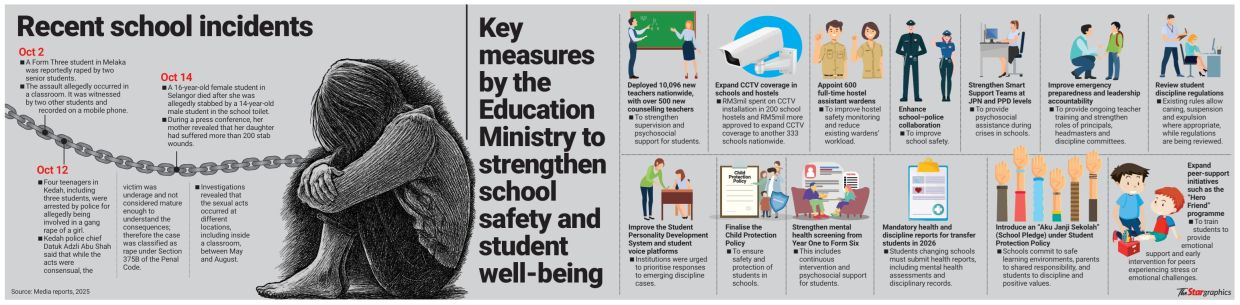

STUDENT violence has increasingly dominated headlines, including reports of sexually aggressive behaviour towards girls in schools (see infographic).

When such cases emerge, public attention often turns to how minors should be held accountable.

However, experts warn that a narrative centred largely on punishment is insufficient to address the root causes of such behaviour or prevent its recurrence.

Amid the Education Ministry’s move to introduce additional measures to enhance school safety (see infographic), Unicef Malaysia education specialist Azlina Kamal said investing in schools as spaces for prevention must be made mandatory, as it is among the most effective, cost-efficient and sustainable ways to protect children and promote long-term well-being.

“When schools are sufficiently resourced, they can move beyond punitive discipline towards restorative responses, allowing behavioural concerns to be addressed early, rehabilitation to take place, and cycles of harm to be broken.

“Expecting children to succeed academically while navigating complex emotions, peer conflict, digital pressures and harmful social norms on their own is neither realistic nor responsible,” she said.

Adding on, Unicef Malaysia child protection specialist Lee Lyn-Ni emphasised that schools play a key role in spotting early warning signs, as children spend much of their day there and such signs often first appear in these environments.

“If risks are not identified and addressed early, harmful patterns can escalate,” she cautioned.

Equipping counsellors

However, even when warning signs are present, schools may lack the capacity to respond effectively, Sunway University School of Psychology senior lecturer Dr Wu Shin Ling pointed out.

She highlighted that the challenges many school counsellors face today are far more complex than their training and workload often allow them to handle.

“Responding safely to aggression, sexual misconduct or severe emotional instability requires specialised skills such as risk assessment, trauma-informed practice, safeguarding procedures, and coordinated intervention with teachers, administrators and external professionals,” she explained.

In reality, Wu added, counsellors are often stretched thin by administrative duties and large caseloads, limiting the time they can devote to these demanding cases.

“This is not a matter of counsellors falling short, but a system that needs continued strengthening,” she said.

“Expanding professional development, providing regular supervision, and ensuring adequate staffing would give counsellors the support they need to handle rising challenges with confidence and safety.”

Echoing this, Lee suggested that linking trained social workers to schools – either through regular on-site presence or clear referral pathways – could help prevent issues from escalating into serious harm or violence.

“Professional social workers bring the expertise needed to assess risk, support children’s mental health and psychosocial needs, work with families, and coordinate timely referrals to health, welfare and protection services,” she explained.

Such an approach, Lee said, would help shift the system from reacting after violence occurs to intervening earlier and preventing it altogether.

Teaching coping skills

Beyond structural support, the experts also highlighted the importance of integrating social and emotional learning into everyday education.

According to Wu, many boys are capable of articulating their emotions when given safe, structured opportunities.

The issue, she said, is often not a lack of feelings, but a lack of emotional vocabulary, permission and practice.

In school settings, this can manifest as behaviour that appears to be a discipline problem but is actually a sign of distress.

“Therefore, this means teaching students how to recognise their emotions, calm themselves, resolve conflicts and repair harm when mistakes happen.

“These skills must be embedded into the curriculum, not used as a form of punishment,” Wu said.

When emotional skills are not consistently taught or reinforced, she said, many students rely on responses that are quick, familiar and socially rewarded – even when those responses do not help them cope in healthy ways.

Instilling values

Meanwhile, Suka Society training and consultancy head Alex Lui added that social and emotional education must go beyond skills training to instil values of respect and dignity.

Suka Society is a non-governmental organisation set up to protect and preserve the best interests of children.

“If we want to teach emotional and social education, we must teach people to value one another for who they are, not for what they can achieve,” said Lui, who is also a registered clinical psychologist.

When schools place disproportionate emphasis on academic performance, he noted, some students inevitably feel unseen, alienated, or defined by failure rather than worth.

”This sense of rejection can push them to seek validation elsewhere – often in negative peer groups – while withdrawing from the adults meant to guide them.

“Notice those who have no reason to be noticed. Make them feel like somebody. Give them a voice and help them find a place in school and in society,” he said.

Without these values being modelled, he warned, students may instead absorb norms from peer cultures that reward dominance and intimidation.

Lessons on consent

Structured and age-appropriate education on consent is also crucial in early prevention, said Azlina.

She suggested that Malaysia would benefit from a nationally consistent framework on consent, power dynamics and gender respect embedded across the education system.

Often referred to as comprehensive sexuality education, she said the concept is frequently misunderstood.

“It is not about encouraging sexual behaviour,” she stressed, adding, “It is about ensuring children understand boundaries, bodily autonomy, mutual respect, equality and healthy relationships – both online and offline – from an early age.”

Teaching children about consent and respect early, she said, also reinforces the principle that every child has both rights and responsibilities in how they treat others and themselves.

Without clear and structured guidance, Azlina warned that children are left to learn about relationships, power and gender norms from peers, social media and online content, which may reinforce harmful or distorted ideas.

Likewise, Wu emphasised that children who learn about emotions and respect between seven and 10 are at a much lower risk of harmful behaviour later on – but only when those lessons are consistently reinforced.

“They need real-world practice, such as role-playing, guided reflection and ongoing reinforcement,” she said, adding that children must also see respectful behaviour modelled by adults at home and in school.

If children hear about respect but see bullying, humiliation or aggression rewarded, she said, the lessons will not stick.