Professional footballer Lucy Bronze, a member of the English women’s national team and London-based Chelsea FC Women, has unlocked a secret for peak performance on the pitch.

“There’s a phase in my menstrual cycle when I’m physically capable of doing more and can train even harder – it’s insane,” she told the magazine Women’s Health UK in the run-up to the 2025 UEFA European Women’s Championship.

“Men, they’re just this baseline the whole time, whereas we can ‘periodise’ training around the four phases of the cycle and get a lot of benefit.

“Research is quite low level at the minute, but it’s like I’ve been given a superpower for a week.”

England later won the Euro 2025 championship, with Bronze playing the entire tournament with a fractured tibia.

Hyped by social media

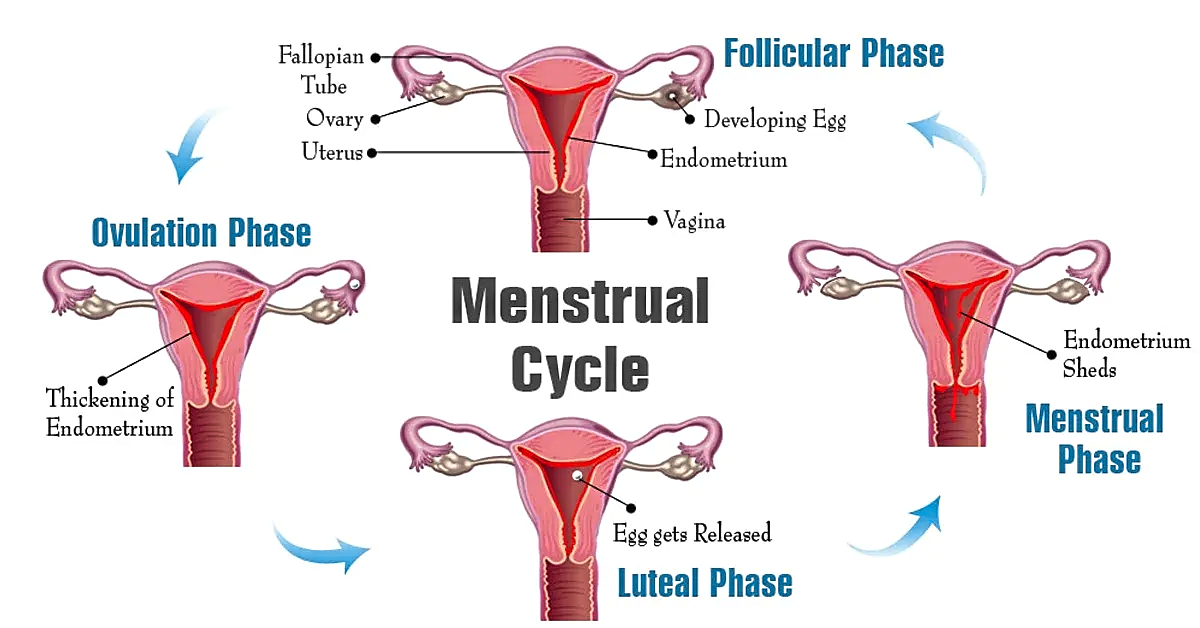

The four phases of the menstrual cycle are:

- The follicular phase: When follicles in the ovaries grow and a mature egg forms

- Ovulation: When an ovary releases the egg

- The luteal phase: When the egg travels through the fallopian tubes to the uterus, and

- Menstruation: When the lining of the uterus sheds through the vagina if the egg isn’t fertilised.

Sometimes, the menstrual cycle is divided into two phases: the follicular, which begins with the first day of menstruation and ends with ovulation, and the luteal, which runs from ovulation to menstruation.

Many women besides Bronze are convinced that it pays to adjust sports training, and possibly diet too, to align with the different phases of their menstrual cycle and the associated hormonal fluctuations – a practice known as cycle syncing.

A major role is played by social media, on which female influencers and athletes relate their experiences with it and give their followers tips and plans.

Instagram and TikTok posts under the hashtag #cyclesyncing get hundreds of thousands of clicks and are often shared.

In a survey earlier this year (2025) by the German statutory health insurance company KKH, 76% of the respondents reported that adjusting their lifestyle to the phases of their menstrual cycle had a positive effect on their physical and emotional well-being.

Some say yes

Is cycle syncing mainly a product of social media hype or truly a worthwhile practice?

Germany’s University of Freiburg professor of sport psychology Dr Jana Strahler says, “It’s definitely been researched and has arrived in competitive sport.”

The degree to which menstrual cycle-based training has taken hold depends on the discipline, but there’s an awareness of the need to take the menstrual cycle into account, she says.

Although female athletes’ competition schedule can’t be cycle-synced, their pre-competition workouts can, she notes.

“Adjusting sports training to your menstrual cycle is a fundamental development, and it pays off,” she says, noting that the primary female sex hormones oestrogen and progesterone, whose levels fluctuate greatly during the cycle, affect energy levels, the immune system, metabolism and more.

Female recreational athletes could also profit from cycle syncing, she says.

“The most important thing is to track your cycle.”

While the first half of the menstrual cycle – the follicular phase – is suited to intensive strength training, according to Prof Strahler, maintenance workouts or light endurance training is advisable in the second half.

And during your period itself?

“Whatever does you good,” she says.

While some women don’t feel like doing sports at all during menstrual bleeding, for others, the increased circulation and cardiovascular activity during sporting activity relieves menstrual cramps.

ALSO READ: Women, you can work out during your period, but only if you feel like it

Some say no

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 78 studies, published in the journal Sports Medicine, British researchers concluded that “exercise performance might be trivially reduced during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle”.

They describe the menstrual cycle as divided into three phases:

- The early follicular phase: Characterised by low oestrogen and progesterone

- The ovulatory phase: Charac-terised by high oestrogen and low progesterone, and

- The mid-luteal phase: Characterised by high oestrogen and progesterone.

Due to the “low” quality of evidence and “trivial effect” on exercise performance indicated, they said no general guidelines could be formed and therefore recommended a “personalised approach” in adjusting exercise to menstrual cycle phases.

A Canadian-British study published in the Journal of Physiology, involving just 12 participants, found that menstrual cycle phase didn’t influence muscle-building.

“Our data show no greater anabolic effect of resistance exercise in the follicular vs the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle,” the authors say.

Lead author Dr Lauren Colenso-Semple noted that many women may not know in which phase their hormone levels change and when each phase begins and ends, which unnecessarily complicates any adjustments of their sports training.

She added that cycle syncing ignored the variability of menstrual cycle duration, the timing of ovulation and differences in hormone fluctuations – both from woman to woman, as well as from cycle to cycle.

Involving the diet

Despite the inconsistent findings, cycle syncing has been practised in competitive sport for several years now.

Chelsea FC Women is a pioneer in this area: In 2020, the football club started using a specialist app to tailor their training programme around players’ menstrual cycles in an attempt to enhance performance and cut down on injuries.

Cycle syncing can include diet too.

A New Zealand review of published literature on dietary energy intake in various phases of the menstrual cycle found that it appears to be greater in the luteal phase, compared with the follicular phase overall, with the lowest intake likely during the late follicular and ovulatory phases.

Writing in the journal Nutrition Reviews, the researchers caution, however, that the number of studies that have specifically researched these phases is limited, and phase-related differences in energy intake most likely vary both between individuals and from cycle to cycle.

As for specific food recommendations, Prof Strahler says anti-inflammatory items – e.g. linseed, salmon and walnuts – as well as warm dishes, could be helpful during menstruation, while protein and whole grain products are well-suited for the first phase in the cycle.

It’s normal, she adds, that a woman’s appetite is greater during the luteal phase – shortly before menstruation – when their body can require 100 to 300 more calories per day.

Those aren’t hard and fast requirements though, she says, but guidelines that every woman can try out for herself. – By Larissa Schwedes/dpa