Sustainable fashion—words that have been tossed around, taken apart and refitted across the world. A term that I’ve been trying to sit with and understand, as a consumer myself.

Let’s put it on hold.

The fashion industry: cue red carpet, trendy street outfits, Instagram posts with OOTD hashtags—glamour, excess, style and the freedom to express.

But it has its dark side.

I’ve learned that globally, about 92 million tonnes of textile waste is produced every year, cited from The Global Fashion Agenda.

On the other hand, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation reported that between 2000 and 2015, clothing production doubled while the duration of garment use decreased by 36%.

Malaysia faces its own significant challenges with fashion waste as well. In 2021, fabric waste accounted for 432,901 tonnes of the country’s total waste, according to data from the Solid Waste Management and Public Cleansing Corporation (SWCorp) and KlothCares.

That’s roughly enough to fill about 170 Olympic-sized swimming pools with discarded clothes.

We know that much of these end up in landfills, and it can take more than 200 years for textiles to decompose. According to bedding brand Cariloha, cotton gloves take three months to decompose while wool takes up to five years.

Both leather and nylon shoes can take up to 40 years to break down, while rubber boot soles take anywhere from 50 to 80 years to decompose.

It’s also no thanks to today’s dopamine-driven purchases that we’re witnessing, fuelled by the thrill of newness and social media validation.

The rise of fast fashion has stitched its way into our daily lives. Campaigns run by e-commerce platforms and brands alike offer markdowns and flash deals that fuel impulse consumption.

Sellers take to live streams, displaying item after item in quick succession, tapping into the urgency and excitement of the moment. With this level of speed and pressure to purchase, the dynamic fuels short-lived wardrobe trends and an acceleration of the “buy-and-discard” impulse.

Yet, the cycle continues.

Perhaps it is not quite a wake-up call just yet because we are not feeling the heat. We cannot see the effect clothes in landfills have on the climate, to our soil and water.

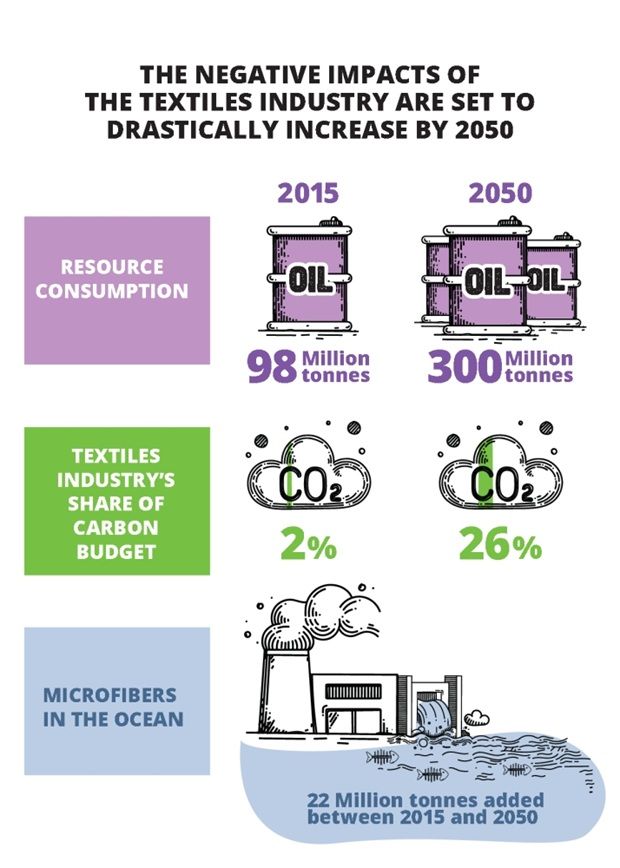

According to a study by Circular Fiber Analysis featured in the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s report A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future, if the fashion industry continues on its current path, resource consumption could triple from 98 million tonnes in 2015 to 300 million tonnes by 2050.

The sector could also account for more than 26% of the global carbon budget associated with a 2°C pathway. Meanwhile, an estimated 22 million tonnes of plastic microfibres could enter the ocean by 2050—adding to the mounting environmental toll of fast fashion.

Good intentions...or not?

We’ve all heard of the 2023 investigation by Swedish paper Aftonbladet who dropped ten items at H&M’s recycling bins and tracked them via AirTags. However, none stayed in Sweden.

Instead, they were transported to Germany for sorting, before ending up in places like Benin in West Africa—where textile dumping and burning are rampant. Even relatively new garments were shredded into fibres, despite claims that they would be worn again.

Still, some local organisations are proving that textile recycling and upcycling can work when done responsibly. Social enterprises have created collection points for fabric waste, turning them into industrial cleaning cloths, blankets or new textile-based products like bags.

Meanwhile, independent designers and thrift boutiques are transforming old clothes into new statement pieces, proving that with creativity and accountability, fashion waste can be given a second life.

Discussions with my teammates led to more learning.

In Japan, the philosophy of mottainai—the spirit of not letting things go to waste—is beautifully expressed in kintsugi, the art of repairing broken pottery with gold, and sashiko, a traditional embroidery technique used to mend worn fabrics with care and pride.

A startup in Tokyo is currently turning discarded kimonos into stylish sneakers as well as leather bags with kimono off-cuts.

Sustainable fashion, I’ve come to realise, isn’t just about turning old clothes into new ones or keeping textiles in circulation. It’s a bigger picture—one that covers how materials are grown and sourced, how garments are made, who makes them, and under what conditions. It includes the social side: the wages, the people and whether brands treat them with dignity and fairness.

In short, it’s about rethinking the entire journey of what we wear without harming both people and the planet.

This prompted me to do a mental check of my wardrobe. Filled mostly with pants and tees; the drawers are almost overflowing. But I’m only wearing 10% of the bulk.

What about the rest? They sit in the dark, untouched. Admittedly, I’ve also bought outfits that I’ve only worn once. Not cheap either.

I have sent a few bags of garments for recycling over the years. But perhaps sustainability also means slowing down—in how we buy, wear and value clothes.

It challenges us to invest in fewer, better-quality pieces, to repair instead of replace, and to appreciate the craftsmanship behind what we wear.

A colleague told me about her less than 50-piece wardrobe that has lasted her for years. For homewear, she only has three sets. If she has not worn a piece of clothing for three months, that’s when it’s donated to a social enterprise run by single parents.

Do I want to follow her footsteps?

Maybe it’s also about sending some pieces to our neighbourhood seamstress and tailors to turn them into something else for us to use again.

A seamstress I know shared that she once had a client bring in her husband’s shirt to turn into a little dress for their daughter.

In the business for over 40 years, she said customers today prefer buying new clothes, as it’s often cheaper than altering or redesigning.

“People will only send clothes for altering if they really like the piece, or if it holds sentimental value,” she replied. Redesigning old garments into new ones is rare, as it requires more workmanship and time.

Is that the shift we need? To see clothes not as disposable trends but as things worth keeping, reimagining and cherishing.

Because when we choose to repair or redesign, we are not only saving fabric—we can help keep small local businesses alive and slow fashion down to a more human pace.

It’s time I did my part too, one small stitch at a time, for the sake of Mother Earth.

Maybe I should bring out that dress I have not worn in 20 years.