Yong (left) among trainees at the Taman Cahaya Training Centre weaving baskets as part of their daily craftwork lessons.

THE first thing you notice at the Taman Cahaya Training Centre isn’t the ageing buildings or its quiet compound. It’s the sound – footsteps tapping along concrete, the rhythmic brushing of white canes, voices calling out across the courtyard.

The centre sits in a rural pocket of Sandakan, unassuming and easy to miss: a cluster of modest dormitories and a small hall that looks as if it hasn’t seen fresh paint in years. Yet inside these walls, people come to rebuild their lives from the ground up.

For decades, this has been the only training centre for the blind in Sabah – the one place families turn to when they run out of answers.

Founded in 1969 and operating from 1970, the centre has trained blind and visually impaired Sabahans from every district – some from coastal towns, others from interior villages reachable only after long, winding journeys.

Most arrive unsure, frightened and unused to the idea of stepping outside their rooms.

Many were kept home their entire lives, not out of cruelty but because their families simply did not know what to do.

“We’ve seen parents keep their blind children in small rooms for years,” said centre supervisor Ibrahim Abdul Hamid.

“They weren’t hiding them out of shame. They just didn’t know where to get help.”

He has been with the centre long enough to have witnessed every kind of story: the ones who crept timidly through the gate; the ones who could not even name the food they were eating because no one had ever taught them; the ones who cried the first time they held a cane; and the ones who left as confident adults with their own income, homes and families.

The centre can take only 25 to 30 trainees at a time, each staying for a year.

Nearly 1,800 blind Sabahans have passed through its doors – and almost all left changed.

Training begins with the basics: orientation and mobility. Trainees learn to walk independently, using a white cane to navigate kerbs, staircases, traffic and open spaces.

Every year, the centre runs a statewide White Cane campaign because many drivers still do not know what a white cane means – and accidents involving blind pedestrians remain too common.

Household skills come next: cooking, cleaning, making a bed, washing clothes.

It sounds simple, Ibrahim said, but for someone who has never moved safely in a kitchen, even frying an egg becomes an act of courage.

They also learn gardening, basic IT, craftwork and eventually massage therapy – the most common career path.

About 80% of trainees leave the centre and become masseurs, some opening their own shops, others working in hotels or clinics across Sabah and Kuala Lumpur.

Many have built stable incomes, supported families and carved out an independence they once thought impossible.

But getting them there is never easy.

“I travel deep into kampungs to find them,” Ibrahim said.

“Sometimes parents chase me away with parang because they think I’m trying to take their child. They don’t understand yet that I’m offering a way out.”

Among the current trainees is Rabiatul Adawiyah Abdul Rahman, 33, a soft-spoken Sandakan woman with partial vision who expects her eyesight to deteriorate with age.

“I joined in 2022 after learning about a White Cane Day event. I realised this centre teaches skills that people like me actually need – cooking, craftwork, even Braille.

“If I lose my sight completely one day, at least I’ll still know how to read. I’m expecting it to happen... so I’m getting ready,” she said.

She studied child and family psychology at Universiti Malaysia Sabah but has struggled to find employment. Training at the centre keeps her hopeful.

“The more skills I learn, the more I can survive on my own,” she said. “Maybe one day I can be a teacher, or start a small craft business.”

Another trainee, Nita Yong, 30, from Ranau, is fully blind in one eye and sees only large shapes with the other. Before joining the centre last year, her life revolved around the walls of her kampung home.

“In the village, no one wants to hire someone like me,” she said matter-of-factly.

“There are very few opportunities, and people don’t know how to deal with someone who has vision problems.

“I didn’t have many friends. I didn’t socialise or hang out with others my age because I was treated differently,” she added.

Yong found confidence only after coming to Taman Cahaya.

“Here, I’m not alone. Everyone understands what I’m going through,” she said. “Before this, I barely spoke to anyone. Now I have friends, activities, and I feel less afraid of the world.”

Sometimes, former trainees return to share their journeys.

One of them is Laimin Saganding, who trained here in the late 1980s and now works as a full-time masseur.

“I came from a kampung where we didn’t know anything about independence,” he said.

“But this place changed my life. Once I learned to take a bus alone, walk confidently and earn money, everything opened up.”

Today, he lives in Sandakan and supports himself fully – something he once thought impossible.

But running the centre is a constant struggle.

It operates under the Sabah Society for the Blind and receives only RM50,000 to RM80,000 a year in government allocations, nowhere near enough to cover annual operating costs of RM350,000. The rest comes from public donations – and during the pandemic, even that dried up.

“We almost had to close,” Ibrahim admitted. “But people still helped. Small donations, big donations – they kept us alive.”

Despite the challenges, he continues travelling across Sabah to find more blind individuals who need help, especially those hidden away by families overwhelmed with fear, guilt or confusion.

“I always tell parents: give them a chance,” he said. “One day, you won’t be here anymore. What will happen to them then?”

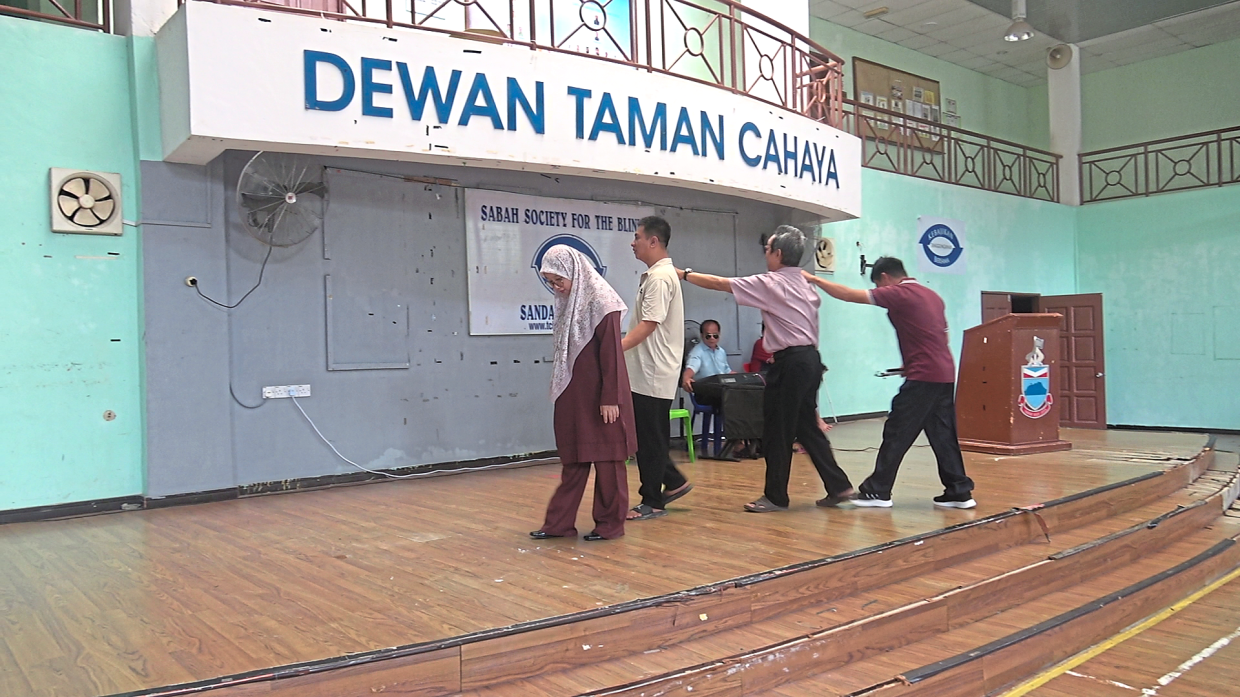

In the hall, a group of trainees laugh as they practise mobility exercises, tapping their canes, counting their steps, learning to hear the world beyond their fears.

Some move slowly, some with surprising speed – but all are reaching for the possibility of a life they can control.

This quiet rural compound, shabby in parts but alive in spirit, gives them that chance. And for many blind Sabahans, it is the first place that ever did.