MALAYSIA is in dire need of psychologists.

The shortage of mental health professionals has been exacerbated by post-Covid-19 issues such as anxiety and stress, as well as a rise in bullying linked to increased social media use.

Describing the situation as “dismal”, Malaysian Mental Health Association president Prof Datuk Dr Andrew Mohanraj said the country, with a population of 35 million, only has 400 clinical psychologists.

That is a ratio of one clinical psychologist for every 87,500 individuals.

“Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation of one clinical psychologist for every 5,000 individuals, Malaysia is far short of the global benchmark,” he told StarEdu.

Sunway University School of Psychology Prof Alvin Ng Lai Oon said the shortage means there are fewer opportunities for people to seek mental health services.

The problem, however, is not a lack of interest in the career, stakeholders say.

They assert that a new generation of psychology students wants to fill that gap, but outdated systems and unfair expectations are stumbling blocks that have caused many to reconsider their options.

Tough road

Interest in psychology is high among students – but channeling that interest into real careers is not easy, said public health researcher Ellern Eng Hui.

He said the challenge starts with the lack of basic protection for those working in the field.

“Despite working to support the mental health of others, we ourselves often lack access to health benefits and job security.

“It’s a difficult contradiction, and one that needs to be addressed.”

The heavy costs involved are another deterrent.

For students like Liong Kah Yan, who is currently pursuing her Master’s in Applied Behaviour Analysis, the cost of studying psychology is steep – and the return is not immediate.

“Internship pays little, if at all. And when you finally find a job, the salary is usually low,” she shared, adding that a postgraduate degree is essential for a stable, better-paying role in clinical practice.

She pointed out that pursuing a master’s degree can cost RM60,000 or more, depending on the course.

“Not many people can afford it, as it is expensive even with scholarships,” she said.

The path to becoming a clinical psychologist, said Prof Ng, is also extremely competitive.

“There are only 12 clinical psychology programmes in Malaysia.

“Even if students get in, the lack of qualified clinical supervisors and practicum agencies makes it tough to gain enough hands-on experience,” he noted.

He added that trainees often struggle to secure placements for their required internships.

“In Malaysia, postgraduate clinical psychology trainees almost need to beg to be accepted as a clinical intern to receive supervised training, and there’s no guarantee that they’ll get the experience they need at a public health service if a supervisor is not available, or if psychological tools are not adequate.”

This bottleneck, he explained, limits trainees’ readiness for real-world practice and narrows their career options.

Still considered a young profession, many experienced clinical instructors are under the age of 40 – leaving a gap in mentorship, he added.

To make matters worse, Liong said psychology students also have to contend with unfair expectations because of their vocation.

“When I tell people that I study psychology, they would pour their whole life story and expect solutions from me.

“This is very unhealthy. Many psychology students are expected to give ‘free’ therapy to relatives, friends or just random people we know,” she said.

Ellern said many people still do not realise that simply holding a bachelor’s degree does not make someone qualified to diagnose mental health conditions.

“Diagnosis is a complex process that should only be done by licensed clinical psychologists.

“It involves detailed assessments, careful observations, and often multiple sessions,” he explained, stressing that it’s not something one can figure out from a five-minute chat.

Fixing the shortfall

Malaysia needs to think beyond traditional methods to close the demand and supply gap for clinical psychologists, Prof Ng said.

Calling for reforms to ensure rigorous clinical training and more structured career pathways, he said competitive salaries and clear progression routes are a must.

“Our salary scale is still under the S-job scheme, when there has long been a call to switch it to the U-job scheme, which offers a higher salary and clinical allowances,” he said.

The U-salary scheme, Prof Ng explained, is meant for clinicians within the healthcare sector like medical doctors, pharmacists and dietitians.

However, clinical psychologists are still categorised under the S-salary scheme, which is meant for social services roles like psychology officers, youth and sports officers, librarians and religious officers.

“The U-salary scheme basically acknowledges that the professional provides services within the clinical and health sector, which is what clinical psychologists are trained to do,” he added.

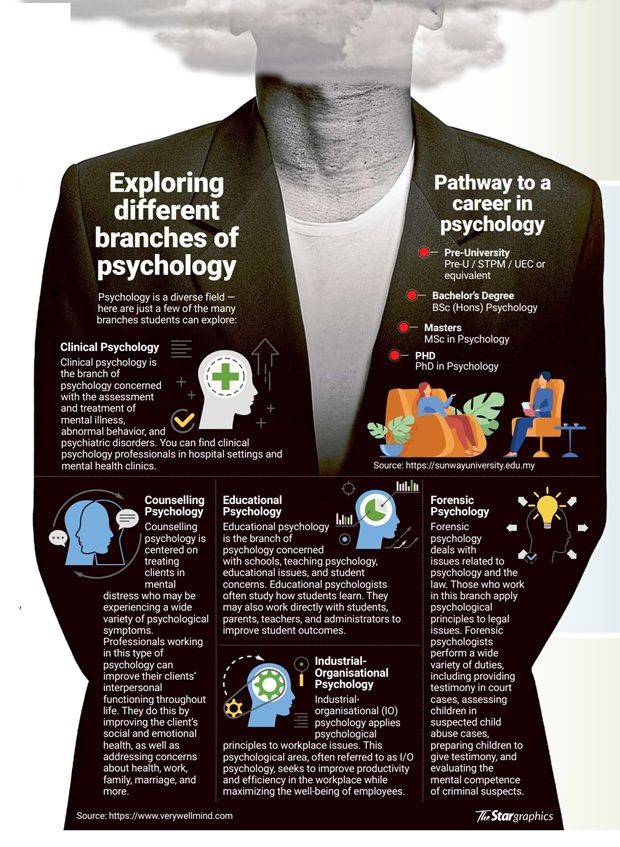

The confusion happens, he said, because many people do not realise that clinical psychology focuses on treating patients, while other branches of psychology like organisational psychology, focus on different areas such as workplaces.

Moreover, he highlighted a system he thinks Malaysia could learn from the United Kingdom’s system – where psychology trainees are automatically employed within the National Health Service, ensuring on-the-job learning while contributing to healthcare services.

Beyond placement and training, Prof Ng said equipping trainees with broader knowledge is equally important.

“I’d also like to see more involvement of medico-legal collaborations so that trainees are also savvy about legal issues and the laws of the land in guiding their clinical decision-making,” he added.

Additionally, he suggested adopting a stepped-care model inspired by the UK’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme.

Under this model, low-intensity therapists are trained in a shorter period – compared to traditional mental health professionals – to deliver basic psychological interventions.

“It’s creating a new layer of professionals who are trained in low-intensity cognitive behaviour therapy that can be used to reduce symptoms of mental health conditions. They are also easier to access and cheaper than the usual mental health professionals,” he explained.

On the other hand, Master’s in Counselling student Tan Xin Yi, suggested implementing initiatives at the school level to draw more young Malaysians into the field.

“Schools can invite counsellors or clinical psychologists to share their experiences and show students what the work really looks like.

“It breaks down misconceptions and inspires students to see psychology as a meaningful career,” she said.

Ellern agreed, as he said that psychology as a field is still relatively new here, having gained traction only in the last 50 to 60 years.

“Public awareness of mental health is still growing, and until it becomes more widespread and better understood, the demand for mental health services (and by extension, careers) will remain limited,” he explained.

Without stronger awareness, Ellern said many people will not seek help, which in turn reduces opportunities for new graduates.

“That lack of demand then feeds into the struggle many psychology graduates face when trying to enter the job market,” he said.