To borrow from poet William Blake’s celebrated 1794 poem The Tyger, India’s tigers are indeed burning brighter in 2025. Following the latest reconnaissance surveys, the country’s National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) recently announced that India’s tiger population has doubled in a decade.

An estimated 3,682 individuals – around 75% of the global population – now occupy over 138,000sq km. Government policies including a clampdown on poaching and the development of tiger “corridors” mean their effective habitat has increased steadily. Moreover, that habitat comprises not just protected areas (such as national tiger reserves) but rural landscapes shared with up to 60 million people.

Just 150km from New Delhi, Sariska Tiger Reserve in northeastern Rajasthan is the closest reserve to India’s capital. For wildlife conservation it’s also become emblematic of how victory can be clawed back from the jaws of defeat.

Originally a royal hunting ground for the maharajahs of Alwar, it was among the first reserves created by Project Tiger in the early 1970s. Yet by the mid-2000s, Sariska’s modest tiger population had completely collapsed. To zero.

Thorough investigations concluded this was largely the result of poachers aided by corruption and apathy. This development – a shock wrapped in a scandal – proved something of a wake-up call for the NTCA and national government.

It led to Sariska’s temporary closure and, nationally, increased powers and funding to thwart poaching and protect habitats.

Yet, even that wasn’t enough; more proactive measures were required. Sariska spearheaded India’s first tiger relocation project starting in 2008 with two males and then a female in 2009. More followed.

Today, in a remarkable turnaround, an estimated 43 tigers including over a dozen cubs call the reserve home.

Standing on Utsav Camp’s terrace near Sariska’s southern boundary, I gazed at the looming hills with anticipation. Luv Shekhawat, its founder, almost has wildlife in his blood. His grandfather, a Forest Department naturalist trained in the last years of the British Raj, imbued him with a sense of wonder and connection with nature that shadowed his early career in tourism.

In 2015 that career took a new turn with his launch of Utsav’s stone cottages and upscale tents tied to an almost holistic take on the region. Staying here, you’re encouraged to walk in the surrounding bouldery hills for their birdlife (there are over 280 species), furtive jackals, stealthy leopards and even rock cupules carved by ancient man.

Plus al fresco breakfasts by rustic lakes, sundowners and even horseriding.

Solar power, filtered water instead of single-use plastic, in-house composting and almost botanic-like gardens – Luv planted over two dozen species of tree including mango, lemon and guava – bolster its eco-credentials.

Sariska, though, is the main draw and its southern entrance lies just a few kilometres away.

Wildlife spotting, or not

Just beyond the park gate our jeep was already bumping along a gently inclined track towards hills dotted with hardy dhok (or button) and baheda trees. Then climbing more steeply through a thickly forested ridge with bamboo groves, we glimpsed shy nilgai antelopes and majestic sambar deer. Langur monkeys unleashed confetti-like showers of dried leaves as they bounded from branch to bough.

We paused briefly straining to hear their distinctive alarm calls – usually signifying a nearby tiger or leopard – but there was nothing.

Over the years I’ve grown accustomed to being an unlucky tiger spotter. Panthera tigris seems to retreat at my emergence so I’ve cultivated more holistic expectations. It’s true that you’re more likely to see tigers at Ranthambore National Park, Rajasthan’s largest, most famous and popular reserve.

But Ranthambore’s popularity means it’s hardly tranquil while in Sariska it felt like I had the place to myself.

Of its various safari circuits, the busiest generally involve domestic visitors focussing on a clutch of temples and a seasonal waterfall linked to Hindu legends. We headed elsewhere, branching off the main road crossing Sariska and climbed a higher track before descending through a winding ravine.

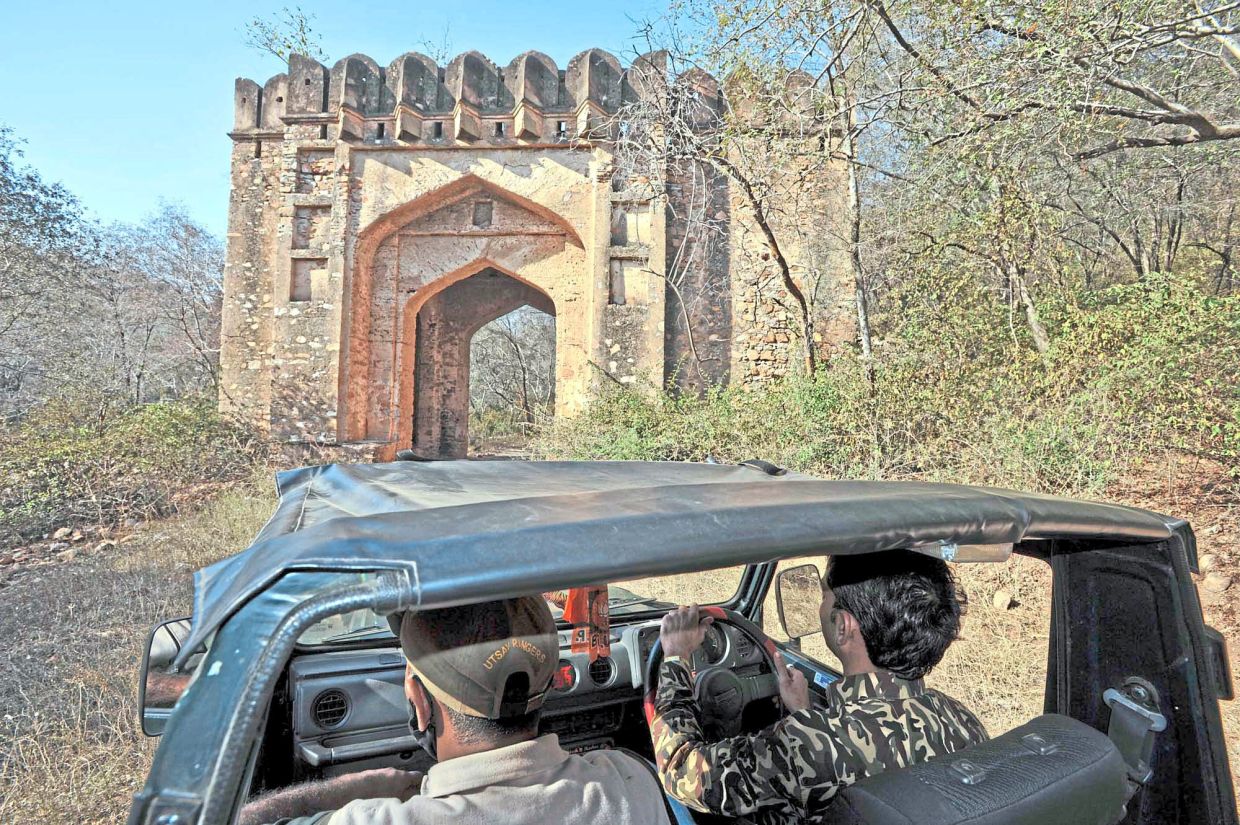

Eventually, it reached a broad almost bowl-shaped valley bristling with palm trees. Topping a hillock up ahead stood ample compensation for not seeing a tiger: Kankwari Fort.

Constructed in the 17th century and then subsequently enlarged by Alwar’s maharajah, this is one of Rajasthan’s least accessible forts. Reputedly it’s also where a young Aurangzeb, the future Mughal emperor, was briefly imprisoned by his brother and rival in their bloody contest to succeed their father, Emperor Shah Jehan.

We gained the hillock, drove through an imposing gateway and then up a fortified ramp to the main entrance. Barely a year earlier, startled visitors stumbled upon a leopard with her cubs occupying a side room just inside; now the gate’s supposed to remain firmly shut.

Thanks to recent restoration work, the fort’s still in good condition. Untended ornamental gardens grace its lower terrace. Above this stands the diwan-i-khas, or hall of private audience, framed by open pavilions and backed by various halls and small courtyards with traces of floral wall paintings.

The complex retains its muscular crenellated walls and a couple of deep wells.

We paused on the roof for tea and snacks. Breathtaking vistas across the valley take in much of the national park and tiger reserve along with the Aravalli Hills stretching to the horizon.

A driveable track continues south through the valley to Neelkanth, an ancient cluster of Shiva temples and shrines standing in Sariska’s buffer zone. But visitors cannot drive this way so we returned the way we had come.

Next morning we set off for Neelkanth on the authorised route. A tarmac road with panoramic views wriggles up the hillside before descending into an elevated valley. This was probably the heart of Rajorgarh, a millennia-old kingdom about which little is known, but its scattered remains of dozens of venerable temples lend the area an enigmatic allure.

The Mahadev temple in particular stands out. It might not look like much from the outside but its interior’s 10th-century carvings and sculpture are beautifully accomplished, ornate and remarkably well preserved.

Luv explained, the resident priest – still attending to a regular stream of pilgrims – is the 15th generation of his family to have that role since the heyday of Alwar’s maharajahs. Local stories largely attribute the temple’s survival despite Aurangzeb’s notorious temple-bashing to a swarm of bees that attacked and saw off his rampaging troops.

Many other temples, shrines and even sculpture dot the site – all now documented, catalogued and probably secure. But for decades if not longer the place lay half-forgotten and an easy target for thieves and smugglers.

Spirited away

Despite the absence of electricity and water, the adjacent villagers seem unlikely to leave this tranquil idyll and their plots of winter wheat, vegetables and tobacco.

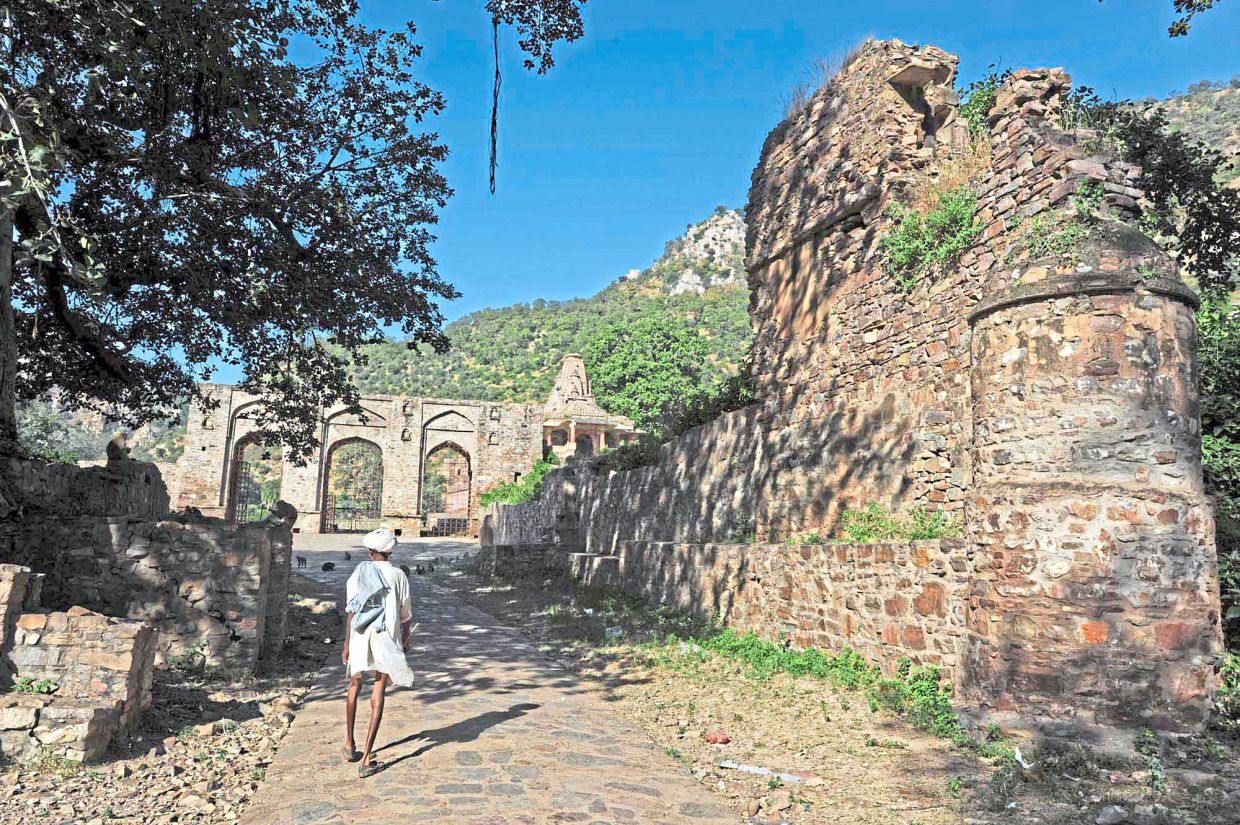

Barely 30km southwest, the medieval fortress-town of Bhangarh had little problem losing its residents. Reputedly the “most haunted place in India”, a much-celebrated Archaeological Survey of India sign strictly forbidding visitors between sunset and sunrise seems to have disappeared.

Bhangarh’s “ghost-town” reputation stems from local lore involving a philandering priest, a princess, potions, black magic and a curse. The 17th-century fortified town and palace was probably emptied in the early 1700s because of strife but tales of its precipitous abandonment and eerie hauntings have endured.

Whatever the case, its picturesque setting at the foot of rugged hills makes it well worth a visit even if the 9,000-plus homes have long crumbled. Once lined with medieval shops and a market, Bhangarh’s main cobbled street leads straight into its heart.

Today, only the main gateways, bastions and some pretty temples survive along with a few ragged havelis, or mansions. At its head stands a once-imposing four-storey palace complex, the roof still accessible.

Off to the right, a domed watchtower tops a lofty ridge; bolder visitors sometimes scramble up here for an eyrie-like panorama. To the left a stream emerges from a slender gorge and palm grove to feed a water tank still used by locals for bathing.

Monkeys cavorted playfully in the trees against a backdrop of screeching parakeets. I strolled into the rugged gorge heading beyond the lush glade at its mouth. Very quickly it became utterly still and silent.

And then I stopped.

Tigers? Leopards? Ghosts? Djinns? Well, out here you never know ...

Travel notes

How to get there: The nearest international airport is in Jaipur, and AirAsia flies there direct from Kuala Lumpur; it is about a five-and-a-half hour flight. Flights from other airlines are also available from KL, with one or two stops in between.

Websites: Utsav Camp (www.utsavcampsariska.com) and Sariska National Park (www.sariskanationalpark.co.in)

Exploring Rajasthan's Sariska Tiger Reserve and Bhangarh

If you're headed to Neelkanth, make sure you go on the 'authorised' route.

— Photos: AMAR GROVER

Why walk when you can just drive up to the Kankwari Fort?

— Photos: AMAR GROVER

Kankwari Fort, Sariska.

— Photos: AMAR GROVER

Utsav Camp is located near Sariska’s southern boundary.

— Photos: AMAR GROVER

The medieval fortress-town of Bhangarh is close enough for a day trip from Sariska.

— Photos: AMAR GROVER

Bhangarh is said to be the 'most haunted' place in India.

— Photos: AMAR GROVER