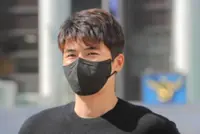

Cho Bum-hee is the main caregiver for his bedridden mother. - The Korea Herald/ANN

SEOUL: Cho Bum-hee was 23, preparing to return to college after completing his military service, when his mother suffered a brain haemorrhage in 2015.

With his father and older sister both working full-time, the responsibility of caring for his mother, whose arms and legs were paralysed, fell to him.

“My mother gave me more love than words can express. I felt it was finally my turn to give back,” Cho, now 34, said in an interview with The Korea Herald.

“My father and sister came to the hospital to help after work, but I handled about 80 to 90 per cent of the caregiving.”

Before he could fully grasp what was happening, Cho’s life began to diverge from his plans and goals. Over the next 11 years of caregiving, the architecture major left college, learnt video editing and started taking on freelance work.

Although he has never regretted the journey, it has been anything but easy.

“Caregiving is physically demanding, but what makes it hardest is the loneliness,” he said.

“You spend so much time caring for a loved one that you neglect your own emotional needs, and there are few people who truly understand what you’re going through.”

Since November 2025, Cho has been sharing his daily life through videos and, in doing so, discovered that many young carers feel just like him.

In his videos, he documents caring for his mother, from helping her eat breakfast and brushing her teeth to spending time together watching TV. Some of these videos have racked up more than 1.5 million views.

“When I felt alone, I wished there were just one person my age in the same situation,” he said.

“I think that’s why my videos resonate with so many caregivers out there.”

A mom, a son and lives of young carers

Cho is one of nearly 15,000 “young carers” in South Korea — people aged 13 to 34 years old who care for grandparents, parents or siblings unable to live independently due to disability, severe illness, alcohol addiction or other health issues.

According to 2024 data from the Ministry of Data and Statistics, 55 per cent of young carers, or 84,347 individuals, are aged 25 to 34, making up the largest share. They are followed by 44,244 individuals aged 19 to 24, or 28.9 per cent. Though they represent the smallest share, a significant number of minors aged 13 to 18 shoulder the burden of family care.

For Cho, caregiving became the defining part of his life on Dec 8, 2015.

The day began in an ordinary way. His mother was at the hardware store his father ran, and Cho was heading to his part-time job.

On the way, he got a call from his mother but hung up quickly to get to work, not knowing it would be the last real conversation they could have.

Found unconscious, his mother was rushed to the hospital and underwent surgery. She regained consciousness but remained unable to communicate.

“Like anyone else, I never thought anything serious would happen to my mother, even though I sometimes imagined things that did not make sense, like her being hit by a car if she came home later than usual,” Cho recalled.

“When it actually happened, it did not feel real. I felt numb more than sad.”

On a leave of absence from college, his life for the next two years revolved around the hospital and home as he cared for his mother practically around the clock, focusing entirely on her recovery.

“Doctors initially said my mother’s chances of survival were less than 30 per cent, and even if the surgery succeeded, she might never regain consciousness,” he said.

“They were surprised by my mother’s recovery.”

After five months at a general hospital, she was transferred to a rehabilitation facility. There, Cho worked closely with specialists, assisting with oral motor, breathing and speech exercises.

Two years after his mother collapsed, they were finally able to remove the tubes in her nose and mouth, used for nutrition and clearing phlegm, and her responses to voices noticeably improved.

As his mother’s condition improved enough for outpatient care at home, Cho resumed his studies in 2020.

With classes having moved online due to the Covid-19 pandemic, he thought he could continue his education without leaving her side. It did not take long, however, for him to realise that architecture was no longer the right path for him.

“I felt I had to start earning money right away to help my father and sister with medical and living costs,” he said, explaining his decision to quit college in his third year.

“Even if I got a job at an architecture firm after graduation, I was concerned that the long hours would make caregiving impossible.”

Instead, he chose video editing. After learning the skills, he took on multiple projects that he could handle from home, primarily editing promotional videos for universities.

For many young carers, education often takes a back seat. Like Cho, they put their studies on hold to care for ill family members, whether voluntarily or out of necessity.

In 2025, the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs surveyed 82 young carers aged 13 to 34 and found that 25 had not studied past high school, and another 16 had dropped out of college.

Long overlooked, the issues of young carers have recently gained prominence.

In 2023, the Seoul Metropolitan Government launched a special unit within the Seoul Welfare Foundation to monitor young carers, along with the operation of support programs.

The foundation conducted consultations with 293 young carers in 2024, offering practical guidance on education and employment, as well as information on caregiving services.

Since 2025, the Seoul city government has offered one million won (US$689) to 1.5 million won in monthly financial support to young carers, based on household income.

More recently, it signed a memorandum of understanding with Lotte Department Store to open counselling centres for those under emotional distress.

Cho voiced hope that information on support programmes would be more widely shared.

“After I shared videos about caring for my mother, the city reached out first to introduce support programmes. Before that, I wasn’t aware such help existed. It’s encouraging to see growing public discussion around the challenges young carers face.

“It would be great to see more gatherings where young carers can share their concerns and information,” he said.

Although his life has taken a different path from many of his peers in their 30s, who are marrying and have families of their own, Cho refuses to let it dampen his spirits, stressing that his life as a young carer has given him a new vision.

“When I stayed with my mum in the hospital, I saw many patients and families doing their best in extremely difficult situations. I want to become someone who could make a positive difference not only for my family, but also for others who need help,” he said. - The Korea Herald/ANN