China is emerging as a rising powerhouse for scientific innovation at a time when scientific research in the United States faces growing funding instability, according to Belgian neurologist Steven Laureys.

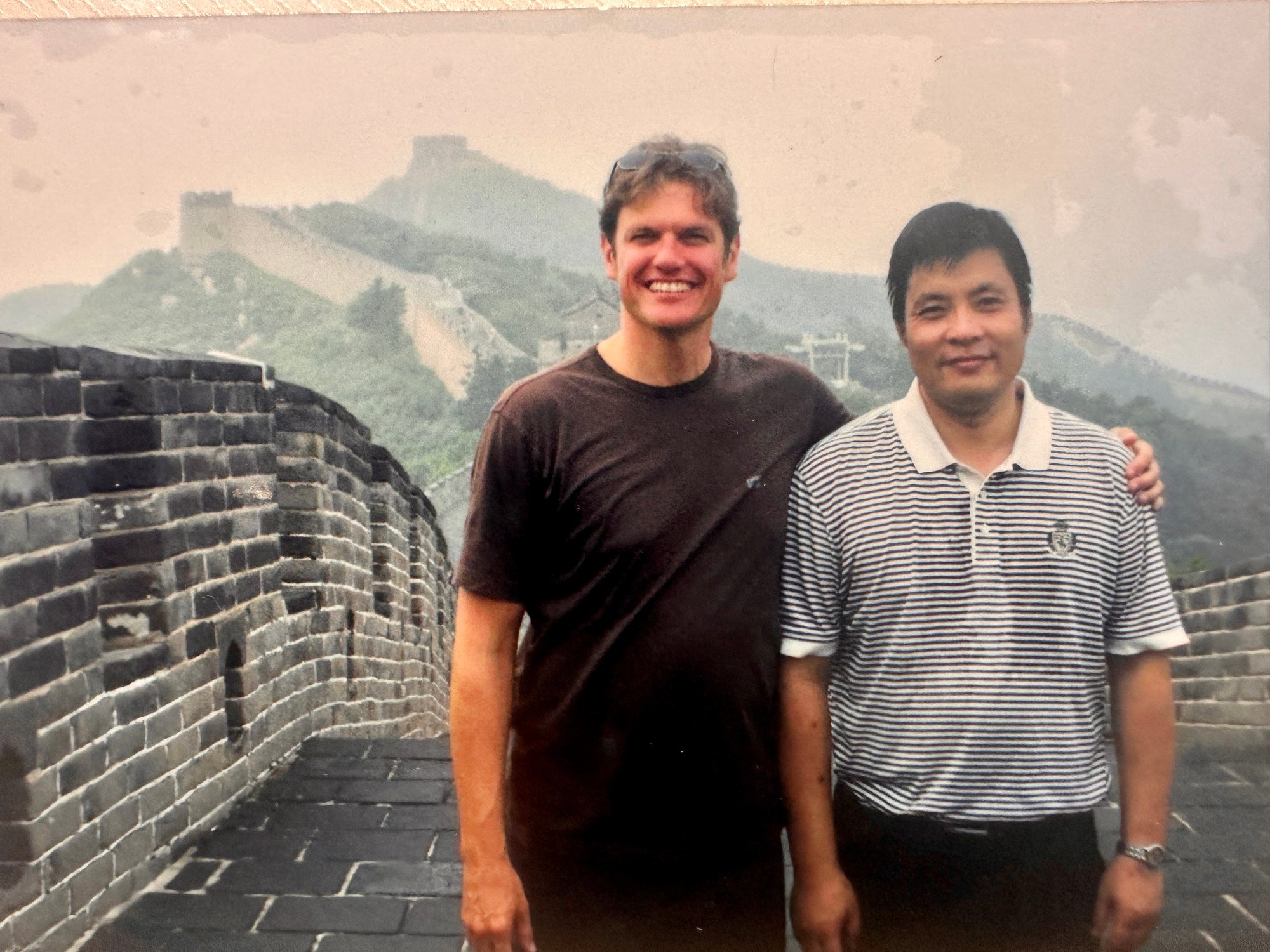

Laureys, a pioneer in detecting hidden awareness in patients with severe brain injuries, is expanding his global research network to China, working with Hangzhou Normal University.

“There’s a wonderful opportunity for me to work with China. And I’m very happy that China is investing in science in these challenging times with [Donald] Trump, because I’m also an invited professor at Harvard. It’s good to see that we benefit from funding there,” he said.

“That’s the power of China – to have this political organisation where, when the decision is made, it happens. The unification of resources and pushing people to work together is very important.”

He said there was “an opportunity also for Europe to react now”, but the continent had not yet developed the unified science policy it needed.

When Laureys began studying sleep and dreaming in the 1990s, consciousness was seen as too subjective and too messy – described by some leading scientists as a “black box” – and research funding was hard to come by.

Three decades later, Laureys is among the world’s leading experts on consciousness disorders and is bringing that expertise to China, a country with one of the largest populations of patients in a coma.

Laureys said such patients should not be described as being in a “vegetative state”, which he described as a “terrible term”.

He argued it wrongly implied that nothing was going on in the patient’s mind, but studies by his team at the University of Liege and others had shown that around one in three patients diagnosed as vegetative may still retain some level of consciousness.

Earlier this year, Laureys took on a research role with Hangzhou Normal University in the eastern Chinese province of Zhejiang. He said the move allowed him to work with a massive, underserved patient population, and to contribute to what he saw as a growing national commitment to neuroscience.

His long-time collaborator, Di Haibo from the same university, said Laureys could have a lasting impact not only on science, but on clinical and ethical decision-making.

“This field is under-addressed in China, partly because of the sheer number of patients,” Di said. While Belgium had a few thousand such cases, China had hundreds of thousands.

Yet national guidelines on how to assess awareness, predict recovery, or decide when further treatment was futile were still lacking, Di said.

“Families are often left to decide everything. Many feel they have no choice but to keep going.”

As a result, many end up losing their loved ones and draining their life savings – and wasting considerable medical resources.

Laureys is now working with Di’s team to build what China has never had: a clear, scientific framework for these cases. That effort will begin with the Zhejiang-Belgium Joint Laboratory for Disorders of Consciousness, the only government-backed research centre in the country focused on this field.

Laureys has also been running a project in Europe and the US to understand the neural underpinnings of business success. He said the evidence pointed towards cognitive flexibility – the ability to adapt to change and make fast, smart decisions – being the key to success.

“I’d love to expand that work to China, because the Chinese culture is so different,” he said. “And Zhejiang is exceptional – Alibaba [which owns the South China Morning Post] is here, and Jack Ma [the company’s founder] came from Hangzhou Normal University.”

When asked about the science of consciousness itself, Laureys described it as “the biggest mystery”. “We’re really very far from an explanatory theory,” he said.

He said the main problem was that people were trying to measure something that was inherently subjective, but added: “It’s a little bit like quantum physics. Your measurement interferes with what you’re trying to measure.”

“It’s easier to put someone on Mars than it is to understand your own thoughts, perceptions, and emotions,” Laureys added. “The more you study, the more you are aware of your ignorance.”

He said his research had deeply changed his outlook on life and death. Laureys has worked with families during the worst moments of their lives – for example, a child hit by a truck, or a partner who collapsed from a heart attack. It put things in perspective, he said. “It makes me appreciate the miracle that life is.”

When Laureys was born – on Christmas Eve in 1968 – both he and his mother nearly died and this had also had a profound role in shaping his outlook.

“She always said, ‘You’re here thanks to medicine. You will give something back.’ So I knew I’d be a physician forever,” he said.

But as a young doctor working in intensive care in Brussels, he often felt frustrated when he was told that coma patients could not feel anything.

“As a scientist, I think you need to be a bit of a rebel. So I questioned that,” he said.

Now in China, he said, he hoped to pass on that spirit to the next generation, and train young researchers to ask tough questions. -- SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST