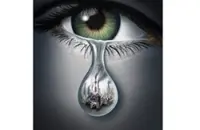

High water: Image from Monday of the city of Navotas, Philippines, after it was hit by Typhoon Fung-wong. Climate change is increasing the severity of weather events like monsoons and typhoons in this region, with cities on the frontlines. — AP

RISING costs of living, relentless traffic, unreliable public transport, choking air, recurring floods, overcrowded homes, water disruptions, and shrinking green spaces are frustrations familiar to city dwellers everywhere.

It is easy to see cities as both drivers and victims of climate change, weighed down by these struggles. Yet taking part in the expert review of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on Climate Change and Cities (SRCC) offered me a deeper perspective.

Being part of this review gave me a rare glimpse into how cities can confront the climate crisis head-on, showing that even amid mounting challenges, there are real opportunities for change.

For those unfamiliar, the SRCC is the only special report to be prepared under the IPCC’s Seventh Assessment Cycle. It represents a major effort to synthesise scientific knowledge on how climate change is transforming urban environments and how cities can lead the way in building resilience and reducing emissions.

Since Oct 17, and until Dec 12, selected experts worldwide will review the draft report to ensure it is both scientifically sound and relevant to real-world urban challenges. Expected in early 2027, the report will be a landmark reference for planners, policymakers, and communities striving to navigate the growing pressures of urban life in a warming world.

While climate change is a global phenomenon, its effects are far from uniform. No two cities experience it in the same way and its impacts are rarely shared equally among urban residents. Coastal cities like Jakarta face rising sea levels and flooding, whereas arid regions like Las Vegas, United States, grapple with heatwaves and water shortages. These stark disparities make it clear that climate solutions cannot be one-size-fits-all or simply copied from one city to another. Instead, effective urban adaptation requires strategies that are tailored to local circumstances, considering geography, infrastructure, social dynamics, and economic context to ensure resilience is both practical and equitable.

In many parts of the world, unequal access to resources has pushed communities to rely on creativity and local knowledge to adapt to climate change. Across South-East Asia, in countries like Vietnam and the Philippines, floating houses made from bamboo and wood have long helped residents cope with floods and rising sea levels. These materials are cheap, accessible, and surprisingly resilient, flexible enough to float with the tides, yet strong enough to withstand the elements.

Today, architects and city planners are taking cues from this ingenuity. Replacing concrete and brick with engineered wood like cross-laminated timber not only stores carbon and provides natural cooling but also delivers the strength cities need. This blend of traditional know-how and modern technology shows that resilience does not have to be expensive. Often, the smartest solutions have been known for generations.

At the same time, cities are beginning to rediscover the power of nature as their first line of defence. Restoring floodplains and rebuilding coastal ecosystems through mangroves, wetlands, and marshes can buffer shorelines from storm surges and erosion far more effectively than concrete seawalls. Prioritising nature-based solutions such as these, along with maintaining urban forests and parks, safeguarding existing green spaces, and enforcing development limits in landslide-prone areas, offers a path toward more sustainable resilience.

Instead of pouring resources into costly, high-tech systems that merely offset climate damage, cities can build lasting protection by working with nature, not against it. In the end, resilience is not measured by how much we spend, but by how wisely we adapt.

CHONG YEN MEE

Kuala Lumpur

The writer previously served with the Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability Ministry and was nominated to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Roster of Experts to review Biennial Transparency Reports and other transparency-related matters of other countries.