A photo of a wolf in the Heiltsuk territory. Here, wolves experience minimal human persecution and disturbance, so they may have more freedom to explore and experiment with new strategies. — Kyle Artelle/The New York Times

WHERE temperate rainforest meets the Pacific Ocean near Bella Bella, British Columbia, the Heiltsuk, a Canadian First Nation, have worked to contain a European green crab problem in their territory.

In 2021, the nation’s Guardian programme, which stewards its traditional lands and waters, began setting traps to remove this invasive species.

But the traps, simple circular, netted frames baited with plastic cups of herring or chopped sea lion, were repeatedly and puzzlingly being torn apart.

Some broken traps lay in deep water, never exposed at low tide.

They thought, “Maybe it’s otters, maybe it’s mink, maybe it’s seals, but we didn’t know,” said Kyle Artelle, an ecologist at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry who works with the Heiltsuk nation.

To identify the crab trap crook, Milene Wiebe, a University of Alberta graduate student, and Richard Cody Reid, a Heiltsuk Guardian, set up a remote camera in May 2024.

What they captured on video the day after deployment was neither a marine mammal nor a mustelid.

It was a wolf.

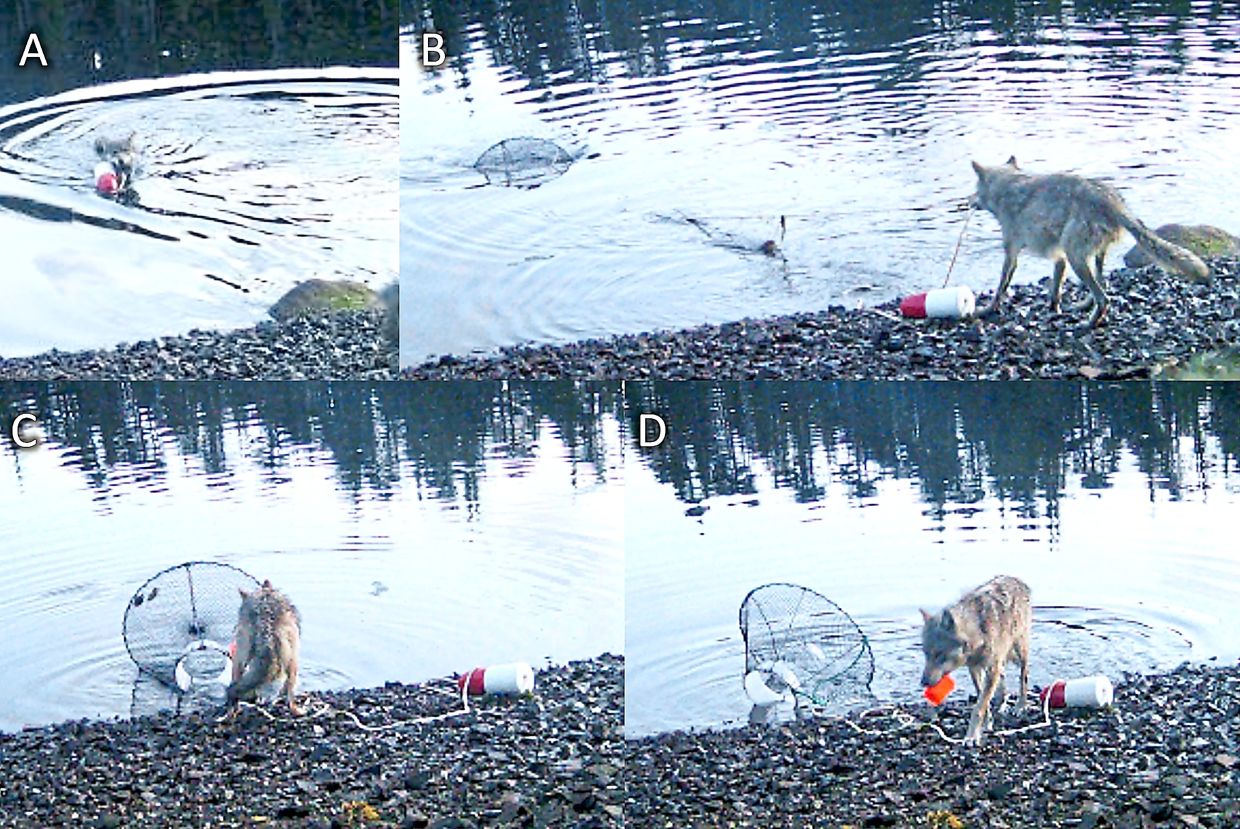

In the footage, the wild canid swims to the shallows from deep water, towing the red and white buoy attached to the trap from her jaws.

She then backs towards shore while raising the rope to the water’s surface. After dropping the buoy and shaking herself partly dry, she returns to the water, gathers another length of rope and pulls again.

On a third pull, the trap rises into water shallow enough for her to grasp the trap itself.

Then, tearing through the netting to reach the orange bait cup, she carries it up the beach, places it upright on the pebbles, licks out the sea lion strips, checks for scraps, gobbles them down and then nonchalantly trots off.

The researchers describe the brief footage, featured in a paper published in the journal Ecology and Evolution, as the first documented instance of a wolf using a tool.

Tool use is broadly defined as employing an external object to achieve a specific goal with intent, said Artelle and Paul Paquet, a predator ecologist at the University of Victoria in British Columbia and a co-author of the study.

Splitting hairs, or, more aptly, unravelling threads, some experts argue that rope pulling should be excluded as “tool use” because humans, not animals, placed the rope.

But whether or not the wolf’s foraging is called tool use, it’s still “incredible behaviour,” Artelle said.

“Even if we don’t want to call it tool use, the fact that the trap was completely underwater and out of sight makes it hard to argue that she didn’t understand the connection between all these steps,” he said.

The wolf completed the sequence in under three minutes, he said, which meant “this wasn’t just random tinkering”.

Artelle suggested that the behaviour was “unwaveringly purposeful”, applying a phrase from a study of tool use in chimpanzees.

Tool use in non-human animals has long been contentious.

“It had long been thought that we were the only creatures on earth that used and made tools,” said the late Jane Goodall, who in 1960 famously observed wild chimpanzees stripping leaves from a twig and then poking the naked sticks into holes in a termite mound for snacking.

Since then, evidence of tool use by octopuses, crows, fish, elephants, crocodiles and insects has dislodged our arrogance that tool use is uniquely human. Nevertheless, scientific debate persists.

To Sabina Nowak, a wolf ecologist at the University of Warsaw who was not involved in the study, the discovery is not shocking.

“They’re so intelligent,” she said.

Susana Carvalho, a primatologist and paleoanthropologist at Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, noted that this observation bolstered evidence that non-human tool use is more widespread than once thought.

What’s important about the new study, she said, is that “another species with complex sociality is capable of innovation and problem solving”.

Carvalho also pointed out, as do the study’s authors, that finding this behaviour on Heiltsuk territory might not be a coincidence.

Wolves in the region experience minimal human persecution and disturbance, so they may have more freedom to explore and experiment with new strategies.

Whether this wolf is a solitary innovator or represents a broader cultural pattern remains a mystery.

But William Housty, director of the Heiltsuk integrated resource management department, suspects multiple wolves are involved.

“You talk to our crew daily, and every day they’re coming in with bait boxes busted open,” he said.

A descendant of the nation’s wolf clan, Housty has great respect for the species and is unsurprised by the wolves’ cleverness.

“Sometimes we forget that the species that exist with us, around us, are just as intelligent as we are,” he said. — ©2025 The New York Times Company

This article originally appeared in The New York Times