Disaster response: Fire and Rescue Department personnel evacuating residents of Rumah Ambrose Ramping longhouse in Selangau, central Sarawak, from rising floodwaters in March. The writer says it's time for a shift to preparedness and resilience training. — The Star

EACH monsoon season, we brace ourselves for the familiar images of flooded towns, displaced families, and schools turned into temporary shelters. And behind these headlines are children whose education, safety, and sense of normalcy are repeatedly disrupted.

This is the reality I have come to reckon with while on my internship with Unicef Malaysia, particularly in assisting its disaster risk reduction (DRR) programme.

The children and young people of today, who make up more than half of the world’s population, are growing up in an era defined by climate change and an increasing number of climate-related disasters. In Malaysia, the 2020 National Youth Climate Change Survey found that 90% of youth have already experienced climate and environmental hazards.

The growing intensity of floods, heatwaves, and other extreme weather events nationwide is threatening children’s safety and wellbeing. Recent analyses by Universiti Teknologi Malaysia highlight that climate-driven floods, such as those that struck Kelantan and the peninsula’s East Coast in late 2024, are becoming more severe and unpredictable due to changing rainfall patterns, oceanic conditions, and phenomena like El Niño and La Niña.

When disasters occur, children are often the first to lose access to essential services such as education, healthcare, and nutrition. Many also find themselves exposed to unsafe environments, particularly those already living in poverty.

Children are inherently more vulnerable when disasters strike, too. This is because they are physically smaller, physiologically less able to regulate heat, dehydration, or disease, and psychologically more susceptible to trauma and distress. These overlapping disadvantages make them among the most at risk during and after disasters.

Working on DRR has given me a new lens through which to understand disasters. I had always associated disasters with lifeboats, evacuation efforts, and the bright orange jackets of rescue teams.

But I have come to realise that there is an equally crucial side to disaster work – one that happens before the tragedy hits. It is about preparedness and resilience-building, especially when approached through a child-centred lens.

Over the past month, I had the privilege of supporting several initiatives aimed at doing just that. One of them was #Bencana-Ready campaign with U Mobile, where we packed emergency backpacks and lifejackets for distribution to schoolchildren in flood-prone areas along the East Coast.

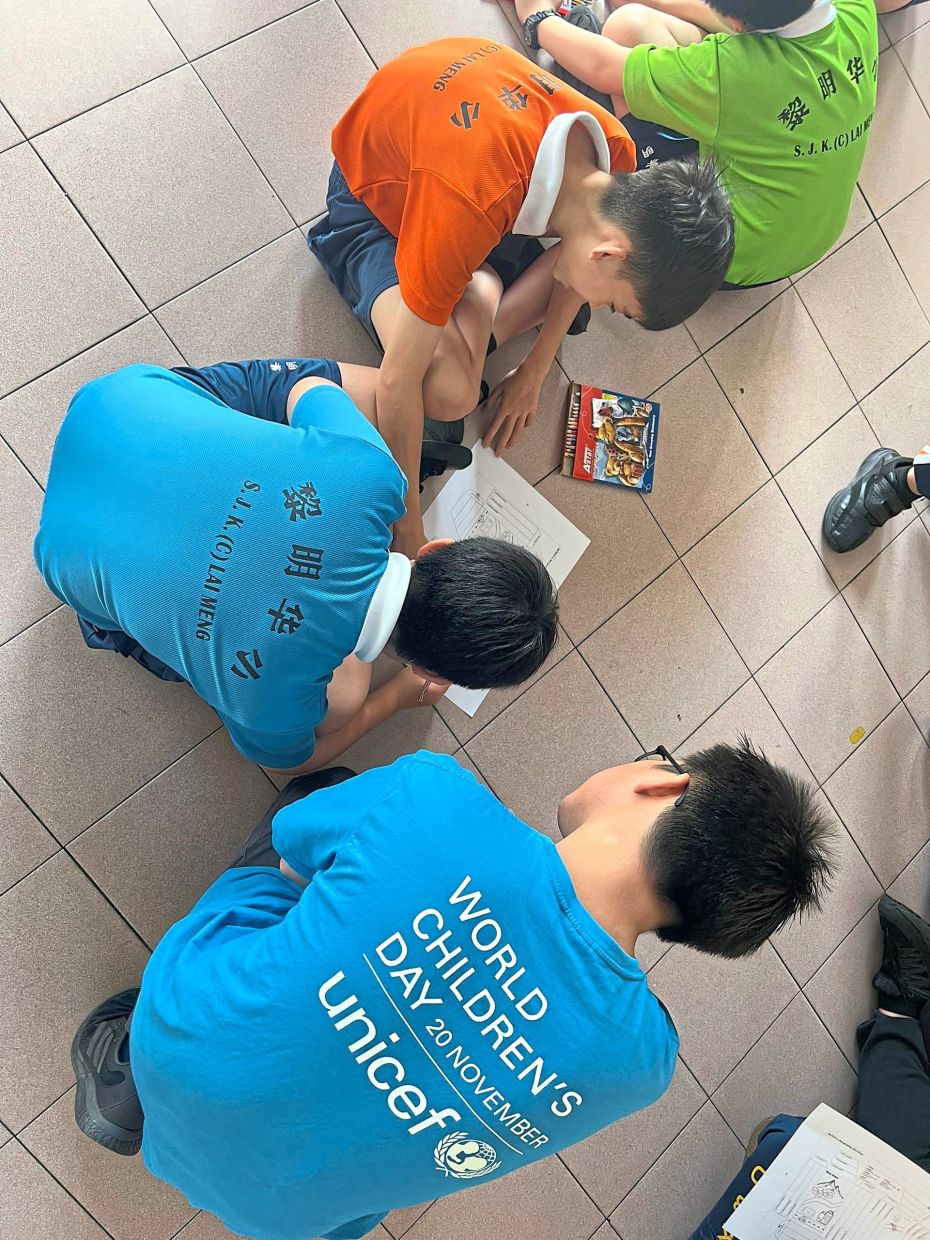

I also witnessed the Training of Trainers for the Disaster Risk Reduction Education Module in Kuala Lumpur, which brought together teachers and students from over a hundred schools across the Federal Territory to learn about DRR.

Being part of these activities made me reflect on what it truly means to be prepared. Watching the children listen attentively to briefings on what to do during disasters and take part enthusiastically in preparedness demonstrations reminded me that resilience is built long before a disaster strikes.

Through these lessons and activities, children learn how to stay safe and also how they can use their knowledge to drive positive change in their communities. Each lesson on resilience carries a belief that every child deserves the knowledge and confidence to face uncertainty.

But disaster resilience cannot be left to teachers, children, and the community alone. It requires support from our policymakers to create an environment where preparedness is prioritised and protection for every child is a shared national responsibility.

To that end, I was able to take part in this year’s International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction exhibition at Parliament on Oct 13. We joined the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Disaster Risk Management to highlight how child-centred resilience and school preparedness can protect lives. Hearing MPs share stories from flood-affected communities was a powerful reminder that building resilience must be a shared effort across society.

Our work would not be possible without strong government partnerships, namely those with the Education Ministry and the National Disaster Management Agency (Nadma) which shared Unicef Malaysia’s vision and co-developed a Disaster Risk Reduction Module under the Safe School Initiative.

The ministry has also been instrumental in rolling out the module nationwide, an initiative that will benefit nearly 7,800 primary schools.

DRR is also beginning to take root as part of the national agenda. In Budget 2026, Nadma saw increased allocations, and funding was also channelled to flood mitigation plan projects and the development of an early warning system.

Moving forward, I urge MPs to shift the national focus from reacting to disasters towards proactively investing in resilience and risk reduction. This means not only strengthening infrastructure and early warning systems, but also embedding disaster preparedness into our national development thinking – from schools and city planning to health systems and community programmes.

Resilience cannot be built by institutions alone. Every Malaysian has a role to play. Whether it’s learning basic preparedness steps, supporting community-based initiatives, or volunteering with organisations that work on disaster awareness, we each have the power to make a difference. For young people especially, understanding the risks around them and knowing how to respond can turn helplessness into empowerment.

At its heart, disaster risk reduction is about protecting the simple joys of childhood: the chance for children to play, learn, and grow without fear. As climate change and increasing disasters continue to disrupt these moments, we need to equip children to survive and thrive. Because in building resilience for every child, we are also safeguarding the future we all share.

Malaysian youth advocate Jonathan Lee Rong Sheng traces his writing roots to The Star’s BRATs programme. The views expressed here are solely the writer’s own.