Jack Posobiec, a far-right political activist, carrying a binder labeled ‘The Epstein Files: Phase 1’ as he exited the White House in February. — Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times)

FOR months, Trump administration officials faced mounting pressure by the far right and online influencers to release the so-called Epstein files, the remaining investigative documents of the sex-trafficking investigation into Jeffrey Epstein, a multimillionaire who hanged himself in a federal jail in New York in 2019.

On July 7, the US Justice Department issued a memo that sought to put an end to the matter, following what it said had been an exhaustive investigation: “This systematic review revealed no incriminating ‘client list’...There was also no credible evidence found that Epstein blackmailed prominent individuals as part of his actions.”

This came at the heels of former White House adviser Elon Musk’s suggestion that Trump was in the Epstein files – a loaded accusation that implies the president might somehow be connected to the financier’s crimes.

Musk, who made the claim after a vindictive online battle with the US president did not offer any evidence, but soon added, “The truth will come out.”

Simply being mentioned in such files does not necessarily mean much. Criminal case files are frequently full of victim identities, and the names of witnesses and other innocent people who came into contact with suspects or evidence in a case.

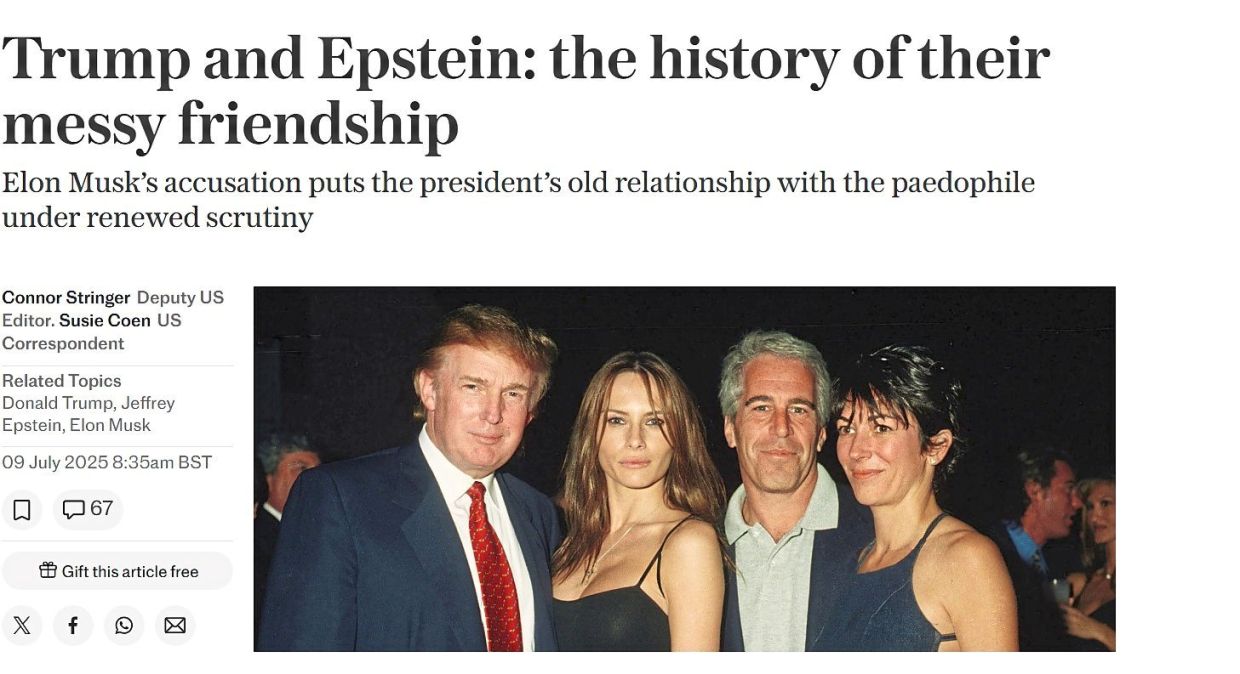

Trump and Epstein had crossed paths over the years, both fixtures of wealthy social circles in New York and Florida. In a 2002 interview with New York magazine, Trump said he had known Epstein for 15 years, calling him a “terrific guy” who was “a lot of fun to be with.”

In that same interview, Trump added, “it is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side.”

In 2019, after Epstein had been arrested again, the president distanced himself. “I knew him like everybody in Palm Beach knew him,” he said. “I don’t think I have spoken with him for 15 years. I was not a fan.”

The Epstein case has long been a focus of self-styled internet sleuths, conspiracy theorists and partisans who try to link Epstein’s crimes to either Democratic or Republican politicians.

It generated intense public interest because the first criminal charges Epstein faced were resolved with an unusual plea agreement, which exacted little punishment for what were described as years of sexual abuse of high school girls whom he paid for “massages.”

In July 2019, Epstein was arrested again and charged with more serious federal crimes. He hanged himself in a jail cell the following month while awaiting trial on those charges. But the handling of his case, and his death, have incited years of speculation that powerful people may have covered up their connections to him, leading to demands that the entire case file be released.

In February, Trump administration officials, including Attorney General Pam Bondi, released what she called “Phase 1” of the Epstein files, which were greeted with scorn and derision when it became clear that most of the material had previously been made public.

Since then, Bondi and FBI Director Kash Patel had enlisted dozens of agents and prosecutors to scrutinise and prepare other Epstein files for release, according to people familiar with the work who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe internal law enforcement operations. “Phase 2” of the Epstein files has not been released.

For months, federal law enforcement officials assigned to the task had wrestled with how to responsibly handle such information, especially when there is a possibility that innocent people named in the documents may suffer significant damage to their reputations when the files are ultimately released.

But the clamour for the files, particularly from right-wing online influencers, has been relentless. Often those demands are for release of a “client list.” That term, however, has little connection to the known facts of the case, in which Epstein repeatedly hired girls to work for him at his homes, giving him “massages” that he quickly turned into sexual acts. — ©2025 The New York Times Company