Oxygen tank strapped to his back, Michael del Rosario moves his fins delicately as he glides along an underwater nursery just off the Dominican Republic coast, proudly showing off the "coral babies” growing on metal structures that look like large spiders.

The conservationist enthusiastically points a finger to trace around the largest corals, just starting to reveal their vibrant colors.

Del Rosario helped plant these tiny animals in the nursery after they were conceived in an assisted reproduction laboratory run by the marine conservation organisation Fundemar. In a process something like in vitro fertilisation, coral egg and sperm are joined to form a new individual.

It's a technique that's gaining momentum in the Caribbean to counter the drastic loss of corals due to climate change, which is killing them by heating up oceans and making it more difficult for those that survive to reproduce naturally.

"We live on an island. We depend entirely on coral reefs, and seeing them all disappear is really depressing,” del Rosario said once back on the surface, his words flowing like bubbles underwater. "But seeing our coral babies growing, alive, in the sea gives us hope, which is what we were losing.”

The state of corals around the Dominican Republic, as in the rest of the world, is not encouraging. Fundemar’s latest monitoring last year found that 70% of the Dominican Republic’s reefs have less than 5% coral coverage. Healthy colonies are so far apart that the probability of one coral’s eggs meeting another’s sperm during the spawning season is decreasing.

"That’s why assisted reproduction programs are so important now, because what used to be normal in coral reefs is probably no longer possible for many species,” biologist Andreina Valdez, operations manager at Fundemar, said at the organisation’s new marine research centre. "So that’s where we come in to help a little bit.”

Though many people may think corals are plants, they are animals. They spawn once a year, a few days after the full moon and at dusk, when they release millions of eggs and sperm in a spectacle that turns the sea around them into a kind of Milky Way. Fundemar monitors spawning periods, collects eggs and sperm, performs assisted fertilisation in the laboratory, and cares for the larvae until they are strong enough to be taken to the reef.

Producing corals

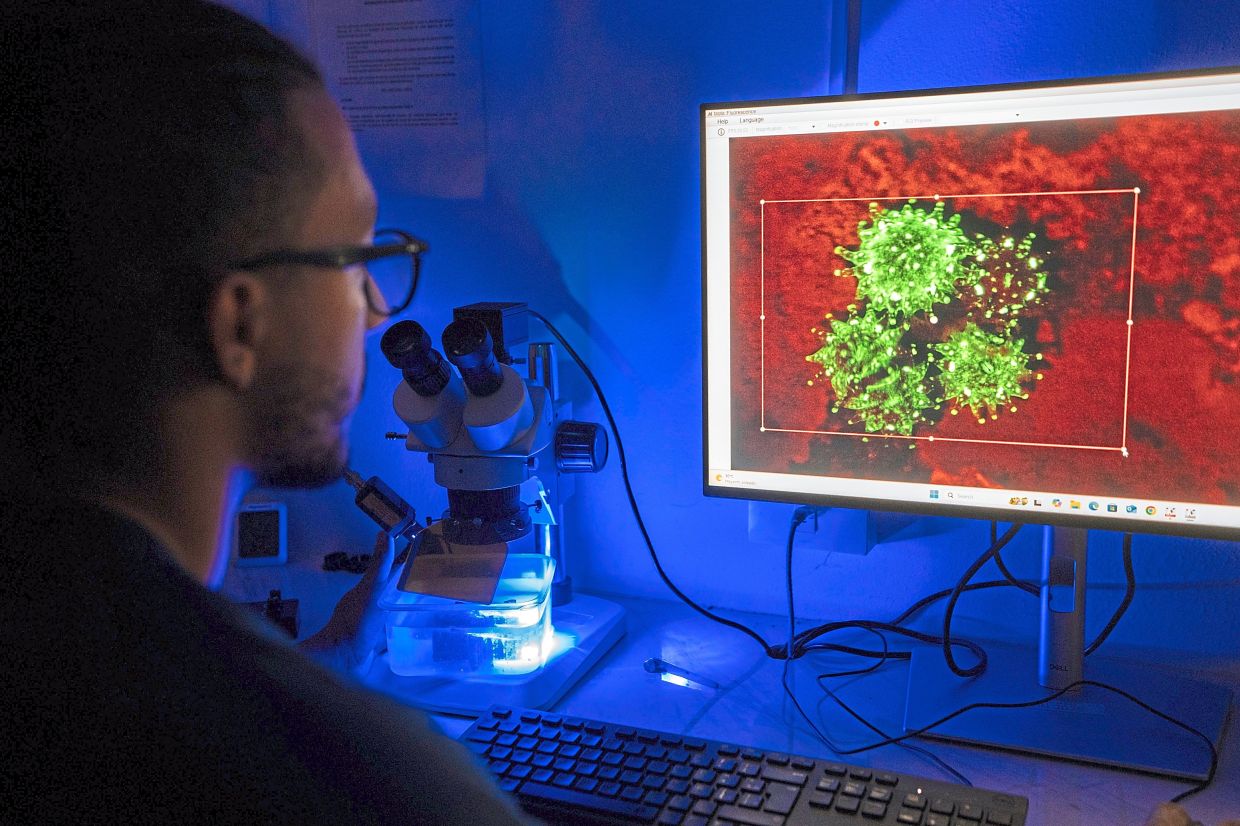

In the laboratory, Ariel Alvarez examines one of the star-shaped pieces on which the corals are growing through a microscope. They're so tiny they can hardly be seen with the naked eye. Alvarez switches off the lights, turns on an ultraviolet light, and the coral’s rounded, fractal shapes appear through a camera on the microscope projected onto a screen.

One research centre room holds dozens of fish tanks, each with hundreds of tiny corals awaiting return to the reef. Del Rosario said the lab produces more than 2.5 million coral embryos per year. Only 1% will survive in the ocean, yet that figure is better than the rate with natural fertilisation on these degraded reefs now, he said.

In the past, Fundemar and other conservation organisations focused on asexual reproduction. That meant cutting a small piece of healthy coral and transplanting it to another location so that a new one would grow. The method can produce corals faster than assisted fertilisation.

The problem, Andreina Valdez said, is that it clones the same individual, meaning all those coral share the same disease vulnerabilities. In contrast, assisted sexual reproduction creates genetically different individuals, reducing the chance that a single illness could strike them all down.

Australia pioneered assisted coral fertilisation. It's expanding in the Caribbean, with leading projects at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and the Carmabi Foundation in Curacao, and it's being adopted in Puerto Rico, Cuba and Jamaica, Valdez said.

"You can’t conserve something if you don’t have it. So (these programmes) are helping to expand the population that’s out there,” said Mark Eakin, corresponding secretary for the International Coral Reef Society and retired chief of the Coral Reef Watch programme of the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

But the world must still tackle "the 800-pound gorilla of climate change,” Eakin said, or a lot of the restoration work "is just going to be wiped out.”

Burning fossil fuels such as oil, gas, and coal produces greenhouse gases that trap heat in the atmosphere, driving up temperatures both on Earth’s surface and in its seas. Oceans are warming at twice the rate of 20 years ago, according to Unesco’s most recent State of the Ocean Report last year.

And that's devastating for corals. Rising heat causes them to feel sick and expel the algae that live in their tissue and provide them both their striking colors and their food. The process is known as bleaching because it exposes the coral's white skeleton. The corals may survive, but they are weakened and vulnerable to disease and death if temperatures don't drop.

Coastal protection under threat

Half the world’s reefs have been lost since 1950, according to research by the University of British Columbia published in the journal One Earth.

For countries such as the Dominican Republic, in the so-called "hurricane corridor,” preserving reefs is particularly important. Coral skeletons help absorb wave energy, creating a natural barrier against stronger waves.

"What do we sell in the Dominican Republic? Beaches,” del Rosario said. "If we don’t have corals, we lose coastal protection, we lose the sand on our beaches, and we lose tourism.”

Corals also are home to more than 25% of marine life, making them crucial for the millions of people around the world who make a living from fishing.

Alido Luis Baez knows this well.

It's not yet dawn in Bayahibe when he climbs into a boat to fish with his father, who at 65 still goes to sea every week. The engine roars as they travel mile after mile until the coastline fades into the horizon. To catch tuna, dorado, or marlin, Luis Baez sails up to 50 miles (80.4km) offshore.

"We didn’t have to go so far before,” he said. "But because of overfishing, habitat loss, and climate change, now you have to go a little further every day.”

Things were very different when his father, also named Alido Luis, started fishing in the 1970s. Back then, they went out in a sailboat, and the coral reefs were so healthy they found plenty of fish close to the coast.

"I used to be a diver, and I caught a lot of lobster and queen conch,” he said in a voice weakened by the passage of time. "In a short time, I would catch 50 or 60 pounds (22.6 or 27.2kg) of fish. But now, to catch two or three fish, they spend the whole day out there.”

Del Rosario said there's still time to halt the decline of the reefs.

"More needs to be done, of course ... but we are investing a lot of effort and time to preserve what we love so much," he said. "And we trust and believe that many people around the world are doing the same.” – AP