BETTER gender representation is needed in top management positions at public universities.

Not only would this reflect the composition of academics where female lecturers made up almost 60% of educators at these institutions, it would also result in different values and perspectives being brought to the table and this can have important bearings on how the university is run, said Sharon A. Bong, professor of gender studies at Monash University Malaysia School of Arts and Social Sciences School.“Women value people-centreness, question traditional norms that lead to critical and creative thinking and action, foster a more caring work culture and build resilience in meeting global challenges and opportunities. This is evident in their actions,” she said.

Qualified women as leaders, she said, have distinctive attributes that often go unrecognised or worse, trivialised or maligned. “When these attributes are directed at the enterprise of knowledge building and translational research that impact policy and legal reforms, it engenders transformative education,” she explained.

Stressing that it is not about the benefits that women bring to the table, she said the question to ask is what harms are brought about to women, as well as men and other stakeholders involved, in decision- making devoid of equal gender representation.

“When women are not part of the decision-making process in familial, financial, legal, political, religious and learning institutions, the youth in particular, will feel its impact,” said Prof Bong, who is also the graduate research director of the school.

Women in top varsity management, she added, is an indicator of gender parity.

“This is a fundamental human right and is one of 12 critical areas of concern in the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action,” she pointed out.

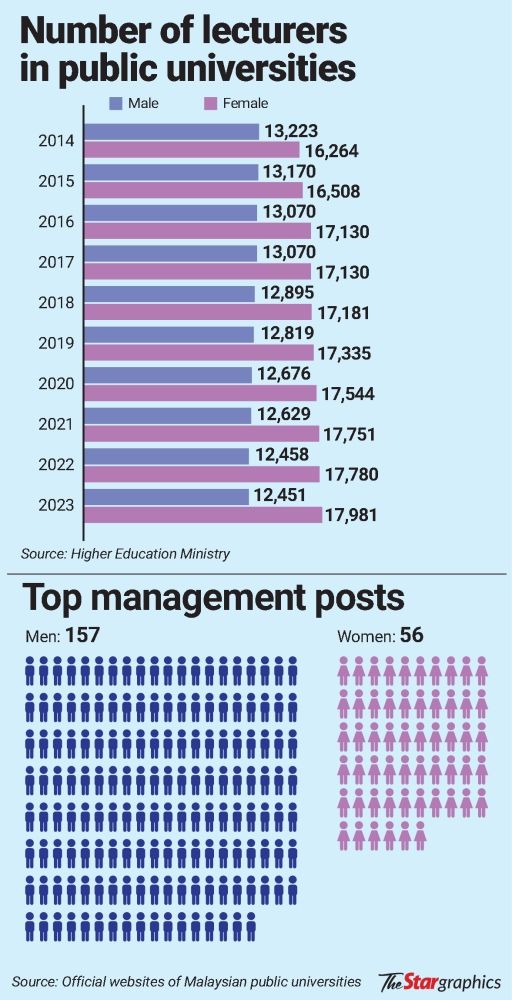

A check on the official websites of the 20 local public universities showed that less than half of the top management or executive committee were women (see infographic).

Last year, female lecturers made up almost 60% or 17,981 of the total 30,432 lecturers in Malaysia’s 20 public universities, with the number increasing over the past 10 years.

Female lecturers rose by 10.6% from 2014 to 2023, based on data from the Higher Education Ministry.

The university with the biggest jump in women was Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, with its female teaching cohort increasing by nine percentage points.

Of the total 213 top posts in the 20 universities, only 35.7% were women, based on a check by The Star at the official website of each of the public universities.

Of the 20 universities, only one currently has a female in the top vice-chancellor position - Universiti Teknikal Melaka.

Top posts include the vice-chancellor (VC) and deputy VCs who oversee student affairs, development, as well as research and innovation.

Commenting on how most lecturers in our public universities are women but it is the men who dominate when it comes to top leadership positions, Prof Bong said the increase in women lecturers at the 20 public universities in Malaysia is likely attributed to a higher percentage of women in Malaysia having tertiary education (47.3%) compared with men (35.8%).

This, she said, was according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report (GGGR) 2023.

She said studies also point to a persistent gender gap in public universities in Malaysia based on the Global Parity Index where female students are not only outnumbering, but also outperforming male students, in many fields of study including in subjects related to science, technology, and mathematics.

A similar trend, she noted, can also be seen globally.

Universiti Sains Malaysia Centre for Research on Women and Gender senior lecturer Dr Zaireeni Azmi said the increase in women lecturers is not a new phenomenon in Malaysia.“Women have been the majority among lecturers in our public and private universities for years now.

“However, while women are the majority in lecturing positions, the same cannot be said for higher academic ranks such associate professors and professors.

“This gap highlights the ongoing challenges women face in climbing the academic ladder,” she said, adding that the situation is the same in many other organisations or institutions where men outnumber women in decision-making positions.

This, she added, indicates the need for continued efforts to address structural barriers, such as promotion opportunities, mentorship, and balancing career and family responsibilities.

Questioning why women are not occupying the highest positions in educational institutions, she pointed to how the majority of teachers and lecturers are women, with more female students enrolling and graduating from universities.

Describing the government’s goal to have at least 30% of top positions filled by women as “helpful”, Prof Bong stressed that other measures must still be in place until the target is met.“Making gender quotas mandatory for a limited period would be a strategic move to complement meaningful longer-term efforts to address systemic discrimination that is levelled not only on the basis of gender but also ethnicity that sustain socio-economic disparities,” she said.

These socio-economic disparities, she added, include women earning less than men for the same job or position, and women being burdened with disproportionate caregiving which results in disadvantageous career breaks.

“Longer-term measures that are aimed at inculcating a workplace culture that sincerely respects diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) are important to avoid tokenism,” said Prof Bong. On Oct 21, Emerita Prof Datuk Dr Asma Ismail, who heads the development of the Malaysian Higher Education Blueprint (MHEB) 2026 - 2035, said one of the key shortcomings identified in the current blueprint, is the lack of emphasis on DEI.

This, she assured, will be addressed in the upcoming blueprint.

She was speaking during the 2024 Academic Convention organised by the Academy of Professors Malaysia, in Putrajaya.

Introduced in 2015, the current blueprint will end next year.It’s crucial to have a diverse leadership team to foster innovation and balanced decision-making. When one gender dominates, it leads to a homogenised environment where certain perspectives are underrepresented. Not only that, gender dominance can perpetuate biases and stereotypes about gender roles, affecting hiring practices, promotions, and the overall culture. If men hold the majority of top positions, it reinforces the stereotype that leadership is a male domain, making it difficult for women to break through the glass ceiling. According to Women’s Aid Organisation’s (WAO) 2021 study on community attitudes, around a third of Malaysians explicitly believe that men make better bosses and should hold positions of responsibility within communities. This bias must be addressed because it can discourage women from aspiring to leadership roles.

— WAO senior research officer (data) Wani Hamzah

If lecturing roles continue to be predominantly female, it could affect the dynamics, development, and diversity of higher education. Education benefits from varied viewpoints and teaching styles, and a dominance of women may limit the representation of male perspectives, especially in disciplines where gendered experiences shape discussions, such as social sciences or gender studies. Female lecturers may also face higher expectations for roles involving student engagement, mentoring, and administrative duties, often perceived as “caring” responsibilities. Socially and culturally, the dominance of women in academia may lead to polarised discussions about gender roles and equality in the workplace, potentially complicating efforts to address systemic gender diversity issues.

— All Women’s Action Society (AWAM) deputy president Khairiah Abdul Malik